Long-Run and Short-Run Determinants of Sovereign Bond Yields in Advanced Economies (except Japan)

by Dirk Ehnts, Econblog101

The IMF has a new working paper out, and the title is the one above except for the term in brackets. As I have often argued here in this blog, I agree with Richard Koo in that Europe is in a balance sheet recession. This means that the private sector wants to deleverage and does not want to borrow more, so government is free to borrow without creating inflation. Nevertheless, in a new paper the summary reads like this (my highlighting in bold):

The IMF has a new working paper out, and the title is the one above except for the term in brackets. As I have often argued here in this blog, I agree with Richard Koo in that Europe is in a balance sheet recession. This means that the private sector wants to deleverage and does not want to borrow more, so government is free to borrow without creating inflation. Nevertheless, in a new paper the summary reads like this (my highlighting in bold):

We analyze determinants of sovereign bond yields in 22 advanced economies over the 1980-2010 period using panel cointegration techniques. The application of cointegration methodology allows distinguishing between long-run (debt-to-GDP ratio, potential growth) and short-run (inflation, short-term interest rates, etc.) determinants of sovereign borrowing costs. We find that in the long-run, government bond yields increase by about 2 basis points in response to a 1 percentage point increase in government debt-to-GDP ratio and by about 45 basis points in response to a 1 percentage point increase in potential growth rate. In the short-run, sovereign bond yields deviate from the level determined by the long-run fundamentals, but about half of the deviation adjusts in one year. When considering the impact of the global financial crisis on sovereign borrowing costs in euro area countries, the estimations suggest that spreads against Germany in some European periphery countries exceeded the level determined by fundamentals in the aftermath of the crisis, while some North European countries have benefited from “safe haven” flows.

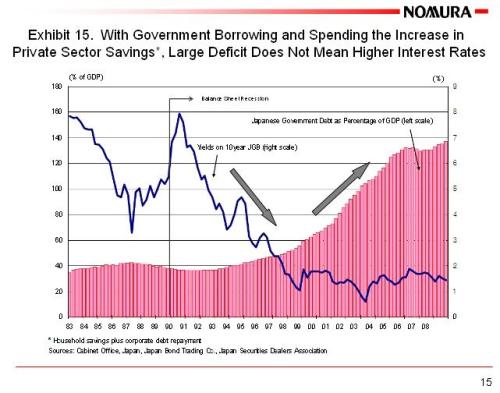

So, let us take a look at Japan, the only advanced economy that had a collapse in both real estate and stock markets for the last 20 years. The slide if from Richard Koo’s Nomura presentation:

So, government debt moves up from 40% to 140% of GDP. That should, according to the IMF study, increase government bond yields by 200 basis points, which is the same as 2%. Being very fair to the IMF, let us look at the yield of 10-year government bonds of Japan. They went down from about 7 to 1.5%, not up to 9% as predicted by the study.

If you search for “Japan” in the IMF paper, it comes up 4 times, 2 times in footnotes and once in the main text and in a table. There is a ‘Japan dummy’ mentioned (see Table 21, for example). I can quite imagine who the ‘Japan dummy’ is here.

Related Articles

Analysis and Opinion articles by Dirk Ehnts

About the Author

Author

Dr. Dirk Ehnts is a research assistant at the Carl-von-Ossietzky University of Oldenburg (Germany). His focus is on economic integration and economic geography, covering trade, macro and development. He is working at the chair for international economics since 2006 and has recently co-authored a book on Innovation and International Economic Relations (in German). Ehnts has written at his own blog since 2007: Econblog 101. Curriculum Vitae.