by Voxeu.org

— this post authored by Paolo Mauro

Policymakers use a well established traditional accounting method to analyse past paths and predict future paths of debt ratios. But the traditional accounting exercises underemphasise the role of economic growth. This column proposes a simple, extended accounting framework to recognise the importance of growth more fully and explicitly. It quantifies the role of economic growth in debt-to-GDP measurement for Ireland and Italy, who were similarly placed in 2012 but whose paths diverged significantly in subsequent years.

Most macroeconomists are familiar with an accounting framework whereby changes in the government debt-to-GDP ratio are split into the contributions of the primary fiscal surplus and the interest-growth rate differential times the debt ratio. This framework is useful for thinking about how past increases or decreases in debt ratios occurred, and to draw possible lessons for the future path of debt ratios (e.g. Reinhart and Sbrancia 2015, Abbas et al. 2014). This issue is important in many advanced economies, where debt ratios rose from an average of 72% at end the end of 2007 to 106% by the end of 2015, largely as a result of the global economic and financial crisis. It is especially relevant in the Eurozone, where the combination of low growth and unsustainable debt persists in Greece, and memories of the interest-debt spiral experienced by Spain and Italy in 2011 and 2012 are still fresh.

The traditional accounting, however, under-emphasises the role of economic growth. When considering the factors underlying changes in the debt ratio, most authors will mention that the primary surplus itself is affected by economic growth, but stop short of quantifying the importance of that additional channel. As a consequence, the impact of growth on debt ratios is not wholly internalised in policy deliberations or analytical discussions. This column proposes an extended accounting framework.

Traditional and extended accounting frameworks

The traditional framework states that the change in the debt-to-GDP ratio equals the primary fiscal deficit (the deficit excluding interest payments on the government’s debt) plus the initial debt ratio multiplied by the difference between the average interest rate on the debt and the growth rate of the economy (the interest-growth differential). A ‘stock-flow residual’ is added to allow for the statistical discrepancy resulting from factors such as debt bailouts of entities that are not part of the general government (e.g. banks and state-owned enterprises), privatisations, or changes in the exchange rate. Output growth erodes the debt ratio because GDP is the denominator in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

The framework can be extended to recognise that the primary surplus (as a ratio to GDP) depends on economic growth. (The extended accounting is derived in Mauro and Zilinsky 2016.) Absent policy measures, economic growth increases tax revenues, but leaves expenditures essentially unchanged. Although this effect is similar to that underlying the ‘cyclical-adjustment’ of the fiscal deficit, economic growth affects the debt ratio through both cyclical factors and changes in the long-run (or ‘potential’) growth rate of the economy. Specifically, in the absence of policy action, it is reasonable to assume that revenues would rise in line with nominal GDP, whereas primary expenditures would rise in line with the GDP deflator1. For example, a ‘neutral policy’ approach would be for the government to raise civil servants’ wages and pensions in line with inflation.

Under that assumption, the primary surplus as a share of GDP would equal the previous year’s primary surplus, plus the product of the growth rate times the ratio of primary expenditures to GDP, plus the effect of policy measures (obtained as a residual). To the extent that the primary surplus rises compared with last year’s surplus by more than implied by the expenditure ratio erosion term, policy measures (whether tax hikes or real expenditure cuts) account for the difference.

Of course, higher revenues resulting from economic growth give governments the option to spend more, and increases in revenues driven by strong economic growth are often accompanied by additional expenditures. But raising expenditures (as opposed to reducing the debt) is a policy choice enabled by economic growth.

It may also be argued that at some point it would become economically and politically untenable for governments to fail to increase real primary expenditures against the background of prolonged economic growth. In a booming economy with rapidly-growing real wages in the private sector, it would eventually become difficult for the public sector to retain its civil servants if their wages lost competitiveness with the private sector. Likewise, rapid economic growth would create its own demands for additional infrastructure spending to accommodate rising usage of transportation services. But governments can choose to resist these pressures for years.

Under the extended accounting framework, the change in the debt-to-GDP ratio would thus equal the growth rate times the sum of the initial debt and primary expenditure ratios, plus the interest rate times the debt ratio, minus the initial primary surplus and the fiscal policy measures taken during the year, plus the stock-flow residual.

The extension is quantitatively important. Take the example of a country where the debt-to-GDP ratio is 80% and primary expenditure is equivalent to 40% of GDP. Considering the change in the debt-to-GDP ratio from one year to the next, the additional contribution of economic growth through expenditure erosion is as large as half of the growth contribution in the traditional accounting approach.

An Illustration

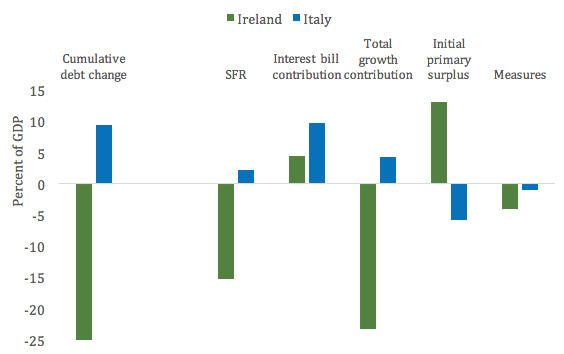

A comparison between Ireland and Italy during 2012-15 is apt because the two countries had approximately the same general government to GDP ratio (about 120% of GDP) at the end of 2012, but they subsequently had vastly different economic growth experiences (4.8% in real terms in Ireland on average during 2013-15, -0.3% in Italy).2 Just three years later, by the end of 2015, Ireland’s debt ratio had fallen to 95%, whereas Italy’s stood at 132%.

This differing performance is primarily attributable to economic growth (Figure 1). Italy also faced higher interest rates than Ireland. These factors more than offset the larger initial primary deficit experienced by Ireland in 2012. After taking into account the impact of economic growth on the primary fiscal balance, policy measures were marginally larger in Ireland, though they were relatively small in both countries.

Figure 1 Cumulative contributions to changes in government debt-to-GDP ratios in Ireland and Italy between end-2012 and end-2015 (in percentage points)

Sources and notes: All data from IMF (2016). The change in the debt-to-GDP ratio is attributed to the various components in identity. SFR is the stock-flow residual.

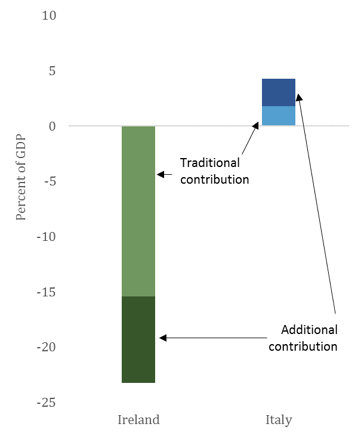

To emphasise the importance of taking into account the fact that rapid economic growth erodes the expenditure-to-GDP ratio, thereby causing the primary fiscal surplus to improve, Figure 2 breaks down the contribution of economic growth into its traditional component and the additional component. The additional component is equivalent to 8% for Ireland (half as large as the traditional component) and to 3% for Italy (larger than the traditional component).

Figure 2 Traditional and additional growth contributions to changes in debt-to-GDP ratios between end-2012 and end-2015, Ireland and Italy (in percentage points of GDP)

Sources and notes: All data from IMF (2016).

As this example illustrates, taking into consideration the role of economic growth in not only eroding the debt-to-GDP ratio directly, but also in giving policymakers the option to let the expenditure-to-GDP ratio be eroded, makes a quantitatively important difference to analysis of overall changes in the debt-to-GDP ratio. Application to the largest increases or decreases in the debt-to-GDP ratios of a large sample of advanced economies in the post-WWII era confirms this finding (Mauro and Zilinsky 2016).

References

- Abbas, S A, N Belhocine, A El-Ganainy, and A Weber (2014), “Current Debt Crisis in Historical Perspective”, ch. 7 in C Cottarelli, P Gerson, and A Senhadji (eds.), Post-Crisis Fiscal Policy, MIT Press, Cambridge MA

- Fatás, A, and I Mihov (2012), “Fiscal Policy as a Stabilization Tool”, The B E Journal of Macroeconomics 12 (3), Berkeley Electronic Press

- International Monetary Fund (2016), “World Economic Outlook”, database, April

- Mauro, P, and J Zilinsky (2016), “Reducing Government Debt Ratios in an Era of Low Growth”, Policy Brief 16-10, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington DC

- Reinhart, C, and M B Sbrancia (2015), “The Liquidation of Government Debt”, Economic Policy, 30, 291–333

Endnotes

- [1] It is assumed that the elasticity with respect to GDP is one for revenues and zero for expenditures. A more refined analysis would recognise that different taxes have different elasticities with respect to GDP (indeed, to different revenue bases, such as consumption for consumption taxes, etc.) and that some expenditures (e.g. unemployment benefits) are negatively associated with economic growth. Nevertheless, these assumptions are reasonably accurate when considering large panels of countries using historical data (Fatás and Mihov 2012).

- [2] The data are drawn from IMF (2016). They do not include a major upward revision to Irish GDP released by the Irish Statistical Office in mid-July 2016, which would strengthen the point made in this column, though at the time of writing it remains to be seen whether the increase in GDP signals a potential increase in tax revenues. The sizeable negative stock-flow residual for Ireland is discussed in International Monetary Fund Country Report No. 15/77, Annex 2

About The Author

Paolo Mauro is currently senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. He was previously at the International Monetary Fund, where he worked for twenty years, most recently as Assistant Director in the African Department. His academic journal papers have addressed topics including corruption, sovereign bond spreads, and growth-indexed bonds. He has coauthored Emerging Markets and Financial Globalization: Sovereign Bond Spreads in 1870–1913 and Today, and led a book project on Chipping Away at Public Debt. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from Harvard University.

Paolo Mauro is currently senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. He was previously at the International Monetary Fund, where he worked for twenty years, most recently as Assistant Director in the African Department. His academic journal papers have addressed topics including corruption, sovereign bond spreads, and growth-indexed bonds. He has coauthored Emerging Markets and Financial Globalization: Sovereign Bond Spreads in 1870–1913 and Today, and led a book project on Chipping Away at Public Debt. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from Harvard University.