from The Conversation

— this post authored by Peter S. Field, University of Canterbury

The idea of “news” is a pretty new thing. So is the concept of “fake news”, as in false or misleading information presented as news. Accordingly, we don’t expect to understand the term outside of our own epoch.

Most people identify “fake news” with Donald Trump, as he used the term widely to challenge mass media coverage of his 2016 presidential campaign. Trump ran as much against the “fake news” of the New York Times and CNN as against Hillary Clinton and the Democrats.

Please share this article – Go to very top of page, right hand side, for social media buttons.

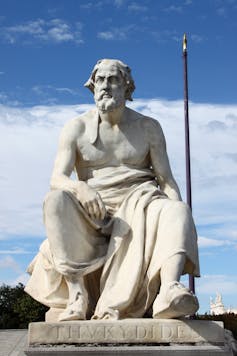

For sure, it’s a long way from Trump to Thucydides, the famous Athenian historian and general. There was no “news” in the ancient world, unless we consider the scuttlebutt in the agora (city square) as a kind of Athens Times or some such.

And poor Thucydides would probably cringe at being compared to Trump. Yet there seems to be a meaningful analogy between Trump and fake news, and Thucydides and myth. More on that in a moment.

shutterstock.

Mistrust and misinformation

By news, we mean something like truth, facts about the world. In that sense, fake news is an oxymoron. News can be false, of course. But we’d like to believe that untrue in this case really means a mistake, a gaffe that in some sense is always correctable. News agencies can and do retract stories and reporters file corrections.

News suggests the default is truth or a commitment to truth. If they are true to their profession, journalists demonstrate a higher commitment or calling, to get stories right, or at least not to fake it. Intentional falsification results in professional suicide.

Fake news is good news: Donald Trump on the campaign trail in 2020. www.shutterstock.com

Which brings us back to Trump and Thucydides. Trump’s brilliance, if we can call it that, was his grasp of a certain presentiment in the American electorate that proved strong enough to catapult him to victory in 2016.

People’s mistrust in institutions seems to be at an all-time high. They feel they are being gaslighted, that there exists a cabal of smug elites who hold them in contempt. As Trump would have it, that cabal includes a press corps, threatened by new media, that has sold out and joined with the deep state and the Democratic Party.

Trump realised he could not become president by preaching to Republicans only, to those who never or almost never voted Democratic. He needed those whose distrust of institutions was compounded by a sense of betrayal.

Read more: An ancient Greek approach to risk and the lessons it can offer the modern world

Declining democracies

The point of all of this is the importance of truth. Real fake news (as opposed to the claim that all news is fake) is about serving up falsehood as truth. No news or fake news in a democracy can be extremely pernicious, as representative government relies on information.

In the US today, a fundamentally ill-informed public produces inferior laws and weak administration. Over time it may well bring about the ultimate disintegration of the democratic regime altogether.

Statue of Thucydides in Vienna. www.shutterstock.com

So, too, went the argument in ancient Athens 26 centuries ago.

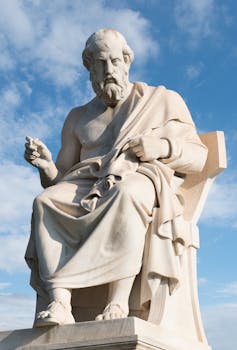

There was no Trump or (fake) news. But there was Thucydides (and Plato) and a democracy that needlessly destroyed itself. By engaging in the disastrous Peloponnesian War, the Athenians forfeited their empire, upended their democracy and lost their freedom.

Thucydides and Plato lived through the crisis of Athenian democracy and, not unlike Trump, informed posterity that the fate of their beloved Athens resulted from the systematic misinformation and mis-education of the citizens.

Read more: Ancient Greeks would not recognise our ‘democracy’ – they’d see an ‘oligarchy’

The wrong myths

Demagogues easily manipulated the Athenian demos (common people), precisely because they had mistaken the fake for the real, because they had been systematically mis-educated. Of course, neither blamed the press or journalists. They blamed the poets.

Statue of Plato in Athens. www.shutterstock.com

Athenians read, or had read to them, Homer and the stories of epic heroes and war trophies and great victories on the battlefield. Thucydides and Plato decried Homer as the fake news of the ancient world. These heroes were the wrong kind and the myths containing their stories had to go.

Plato seemed desperate to displace Homer. His teacher Socrates was offered as an antidote to the sullen, self-centred, violent heroes of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Socrates was a new hero for a new time, a hero of logos (reason) for a new era where the reed would be mightier than the sword.

So too with Thucydides. Throughout his history of war and plague, he demonstrated with scientific observation the futility of appealing to gods and myths. What good did sacrifices to the gods do the Athenians? How did faith in a higher justice serve the Melians or the people of Mytilene?

Homeric fake news doomed the citizenry of Athens to war and decline. Salvation depended on the people dis-enthralling themselves. Survival entailed embracing the logos and adopting a science of society.

The Athenians instead exiled Thucydides and offered Socrates a hemlock milkshake. Trump got off lightly, being merely impeached twice.

This story is based on the author’s public lecture, “Fake news in ancient times: Thucydides, Plato and the expense of truth”, University of Canterbury, February 25.

Peter S. Field, Head of Humanities and Creative Arts and Associate Professor of American History, University of Canterbury

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

.