from Dirk Ehnts, Econoblog101

Relatively unobserved by the media and experts, the establishment of the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) by the ECB has temporarily severely limited the power of the financial markets over national governments in the euro area. The challenge now is to make this permanent.

Please share this article – Go to very top of page, right hand side, for social media buttons.

The ECB’s PEPP is a programme for the purchase of public and private bonds. €750 billion have been earmarked for the first time. The aim is to keep the interest rate premiums of the countries that are particularly hard hit, such as Italy, low. In order to achieve this goal, the ECB has been given great flexibility in the composition of its portfolio and has announced that it is also prepared to implement the programme “by as much as necessary and for as long as needed“.

A look back

Let us remember: in the so-called euro crisis, the ECB felt that it was not responsible for the solvency of the national governments of the euro zone. The solvency of some member states of the European Monetary Union (EMU) – such as Greece in particular, and later also Italy, Portugal, Spain and Ireland – was doubted by creditors. The country code PI(I)GS stood for the group of countries whose government bonds plummeted in price. This was the beginning of the narrative that the euro crisis had been triggered by the crisis countries themselves and not by wage dumping in Germany and real estate bubbles in Spain and Ireland, which were co-fired by German banks.

The problem was this; in a “normal” monetary system, the central bank, as the fiscal agent of the state, also guarantees the solvency of the state. The mechanism is very simple to understand. As a monopolist of the currency, a central bank can produce an infinite amount of money for free. It does this by, for example, buying government bonds from banks. To do this, it credits the banks with the corresponding amount in its account at the central bank.

The money that it spends in so-called “quantitative easing” or also in open market transactions is thus created “out of nothing”. It is not taxpayers’ money, and the central bank does not have to and cannot “finance” this expenditure. It is the creator of the money and, within the rules in force, it can simply increase the balances of the banks and governments’ accounts by typing in the relevant numbers on a keyboard.

Why can the state not become insolvent?

The national government can sell government bonds to banks and they can sell them back to the central bank. Since the central bank can spend an unlimited amount of money to buy government bonds, nothing can go wrong. From the creditors’ point of view, government bonds are risk-free securities. This makes them particularly attractive and banks are happy to buy government bonds from the government. This in turn enables the government to replenish its account with the central bank again and again – which also keeps it solvent.

If this construct still seems too shaky to you, you can oblige the central bank to simply increase the balance of a national government account by a few billion directly, as the Bank of England has just announced.

Since the state is democratically organised in our societies, we have set up our monetary system in such a way that the national government can spend as much money as it has budgeted for (and a little more). But in a state where the national government says we want to spend X and then can’t spend X, there is no democracy. It lacks monetary sovereignty, it lacks access to money, which is needed for government spending. And this money comes from the central bank, because only the central bank is able to create money.

The Corona crisis and the role of the ECB

In the euro crisis, creditors rightly feared that the ECB would not buy Greek government bonds for an unlimited amount. Then, of course, these bonds would no longer be risk-free, but there would actually be a risk of default. So the creditors have sold Greek government bonds. Since hardly anyone wanted to buy them, the price had to fall until supply and demand converged. But lower prices of Greek government bonds inevitably increased the yield of these bonds.

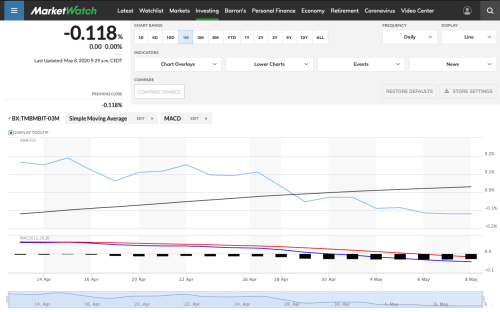

Let us now look at Italian government bonds with a maturity of 3 months. Their yield was around -0.3% to -0.5% until the end of February 2020. This means that creditors (banks) considered Italian bonds to be risk-free in the short term. As the ECB’s deposit rate is currently at -0.5% (with some exceptions), banks are therefore currently indifferent as to whether they “park” money with the ECB or use it to buy Italian government bonds with a 3-month maturity.

From the beginning of March they no longer cared. The prices of Italian government bonds fell, as creditors feared that the Italian state would become insolvent. Yields on Italian government bonds rose to 1% by 18 March. This was the day the ECB announced its PEPP. Creditors quickly understood what this meant: Italian government bonds were risk-free again!

Source: https://www.marketwatch.com/investing/bond/tmbmbit-03m/charts?countrycode=bx

Figure 1 shows that the price of Italian government bonds then moved back down. We are not yet back to the February level, but if the ECB gets serious and buys a sufficient number of Italian government bonds, it will make their price high and pull yields down. The price of Italian government bonds fell as creditors feared that the Italian state would become insolvent. Yields on Italian government bonds rose to 1% by 18 March. This was the day the ECB announced its PEPP. Creditors quickly understood what this meant: Italian government bonds were risk-free again!

This time it’s different

In Southern Europe, including France, there are fears that the corona crisis will once again lead to being forced into austerity policies. However, as long as the PEPP is running, national governments in the eurozone can easily get into debt. They simply spend more money. They do not need corona bonds, Eurobonds, or debt relief to do so. The ECB is aware of its role and is ready to play it:

“The Governing Council will do everything necessary within its mandate.”

This is the end of financial markets’ power over national governments. This is a very positive development that makes a repeat of the austerity policy after the financial crisis at least less likely.

The other problem that countries see is the Commission’s deficit limits. However, these have been suspended for the time being. It is up to politicians to adjust these two parameters – the stabilisation of the ECB’s PEPP and the abrogation of the deficit limits. We urgently need a broad public discourse on these issues to ensure that market fundamentalists do not turn the wheel back again.

- Appeared at Econoblog 101 11 May 2020.

- Appeared in German at Makroskop 21 April 2020.

.