from the St Louis Fed

— this post authored by Michael McCracken, Assistant Vice President and Economist; and Aaron Amburgey, Research Associate

In August 2020, the Federal Reserve announced a change in its approach to monetary policy and how this relates to its mandate of price stability. Previously, a 2% inflation target meant that if inflation started to rise toward 2%, the Federal Reserve would raise the federal funds rate (FFR) to prevent inflation from overshooting 2%. In practice, this strategy not only prevented inflation from rising above 2% but also kept inflation from even reaching 2%. It is also believed that this approach to price stability hampered employment growth, particularly for low- and moderate-income communities, by slowing economic growth more generally.[ 1]

The Federal Reserve now intends to implement a strategy called flexible average inflation targeting (FAIT). Under this new strategy, the Federal Reserve will seek inflation that averages 2% over a time frame that is not formally defined. This means that after long periods of low inflation, the Federal Reserve will not enact tighter monetary policy to prevent rates higher than 2%. One benefit of this flexible strategy to managing the mandate of price stability is that it will impose fewer restrictions on the mandate of full employment.

Determining Average Inflation

But what constitutes an average of 2%? Obviously, there are many configurations of numbers that have an average of 2. Ignoring the configuration in which all the numbers are exactly 2, the remaining configurations must have at least one value that is greater than 2. This matters because these numbers reflect measurements of consumer price inflation, which constitutes an erosion of purchasing power for households despite the potential benefit to employment growth.

Perhaps more than ever, this strategy requires the Federal Reserve to pay attention to inflation forecasts, particularly with an eye toward any indications that inflation is rising above 2% and perhaps staying there, on average, for longer than desired. As an example, suppose that inflation were currently predicted to average above 3% for the next five years. While FAIT doesn’t explicitly define the time frame over which inflation is averaged, five years seems to be too long, and we would expect the Federal Reserve to eventually enact tighter monetary policy to prevent this from occurring.

But how likely is this event? If it has only a 1% chance of occurring, it seems doubtful the Federal Reserve would be concerned. On the other hand, if it has a 40% chance of occurring, it seems very likely the Federal Reserve would be concerned.

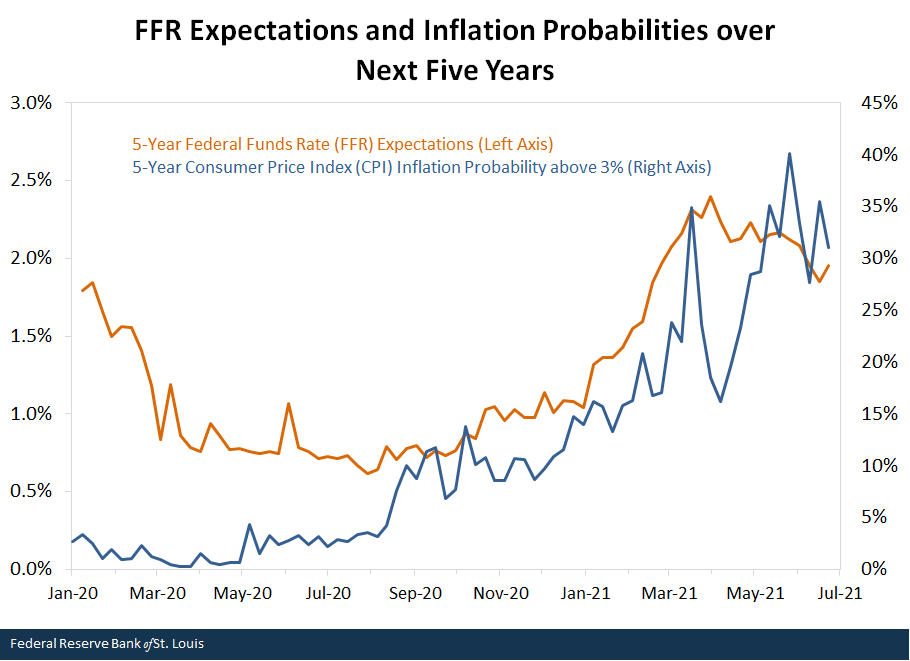

In the figure below, we plot the market-based probabilities that consumer price index (CPI) inflation [2] will average above 3% over the next five years, along with federal funds rate expectations over the next five years. The inflation probabilities are constructed using inflation caps and floors, which we discussed in more detail in a previous blog post. The FFR expectations are constructed using three-month Eurodollar futures and represent what the markets expect the FFR to be in five years. Each of these lines tells us what the markets expect for a given date. For example, in the first week of October 2020, the markets were acting as if the probability of CPI inflation exceeding 3% over the next five years was 7.7%.

SOURCES: Bloomberg and authors’ calculations.

NOTE: The last reported values were for the week of June 25, 2021, with a five-year inflation above 3% probability of 31.1% and five-year FFR expectations of 2.0%.

Focusing first on the blue line, we can see that the risk of higher inflation has steadily increased since the start of the COVID-19 recession. Specifically, between April 2020 and May 2021, the market-based probability that five-year inflation would exceed 3% increased by 38.6 percentage points, from 1.5% to 40.1%. But why? The simplest explanation is that the rate at which prices increase has been accelerating. If the rate of inflation is increasing today, markets might expect this trend to continue.

Since year-over-year CPI inflation bottomed at 0.22% in May 2020, inflation progressively increased to a rate of 4.9% just one year later.[4] Increasing demand, often coupled with supply chain issues, for products such as oil, steel and plastics has driven prices up. Another explanation for a high perceived risk of future inflation has to do with the Biden administration’s $6 trillion budget proposal announced in May, which could spark buying activity that would further increase prices. Most recently, there was a sharp decrease in five-year inflation probabilities from 40.1% to 31.1% in June 2021.

If we shift focus to the orange line, we can see that markets’ expectations of the future FFR have similarly increased since the start of the recession. From April 2020 to June 2021, the future five-year FFR expectations increased by 1.2 percentage points, from 0.8% to 2%. In fact, the correlation between the two plotted series was 0.88 since April 2020. This makes sense intuitively – as the risk of future higher inflation increases, the likelihood that the Federal Reserve will need to tighten interest rates in the future also increases.

Probabilities in a Shorter Time Frame

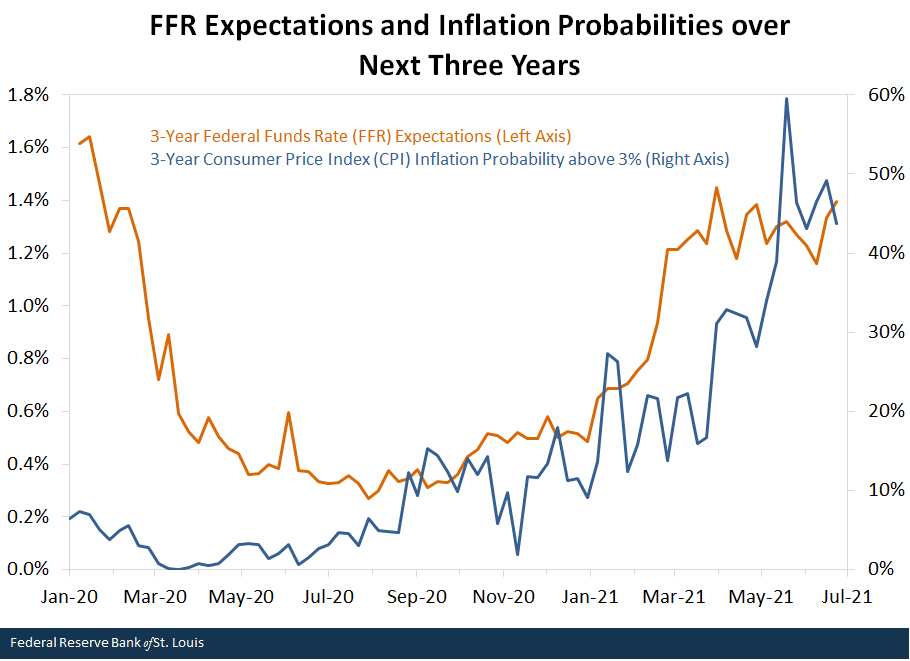

In the figure below, we plot the market-based probabilities that CPI-based inflation will average above 3% over the next three years, along with three-year FFR expectations. In broad terms, this second figure tells the same story as the first. Markets think that the risk of higher inflation has risen and that the Federal Reserve will need to tighten interest rates in the future. In fact, insofar as the Federal Reserve typically raises the FFR in increments of 25 basis points, the current FFR expectations for June 2024 suggest markets believe policymakers will raise the FFR five times over the next three years from 13 basis points to 138 basis points.

SOURCES: Bloomberg and authors’ calculations.

NOTE: The last reported values were for the week of June 25, 2021, with a three-year inflation above 3% probability of 43.8% and three-year FFR expectations of 1.4%.

Testing the New Framework

The Federal Reserve has enacted a new approach to managing their mandate of price stability. At the time FAIT was announced, inflation was muted and had been so for quite some time. In such an environment, it’s easy to predict that monetary policy will not tighten as inflation rises toward, and above, the 2% target. But now that inflation has already risen above 2% and markets assign a roughly 50-50 chance that CPI inflation will average above 3% for the next three years, the FAIT strategy will be tested.

Notes and References

- This strategy is sometimes prosaically referred to as “Taking the Punch Bowl Away Just When the Party is Getting Good.”

- While this analysis is based on CPI inflation, the Federal Reserve targets personal consumption expenditure (PCE). Nonetheless, CPI closely tracks PCE.

- It’s worth noting that the recently high inflation rates in March, April, May, and June 2021 are partly due to what’s called the base effect (i.e., inflation was low for those months in the previous year, so arithmetically smaller rises in the CPI will seem larger than they are).

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Market-Based Measures of Inflation Risks

- On the Economy: How COVID-19 May Be Affecting Inflation

Source

https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2021/july/inflation-expectations-fed-new-monetary-framework

Disclaimer

Views expressed are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or of the Federal Reserve System.