by Jayati Ghosh, Triplecrisis.com

There was a time when economists were inevitably concerned with development. Early economists of the 16th and 17th centuries to those of the mid 20th century were all essentially concerned with understanding the processes of economic growth and structural change: how and why they occurred, what forms they took, what prevented or constrained them, and to what extent they actually led to greater material prosperity and more general human progress.

And it was this broader set of “macro” questions which in turn defined both their focus and their approach to more specific issues relating to the functioning of capitalist economies.

It is true that the marginalist revolution of the late 19th century led economists away from these larger evolutionary questions towards particularist investigations into the current, sans history. Nevertheless it might be fair to say that trying to understand the processes of growth and development have remained the basic motivating forces for the study of economics. To that extent, it would be misleading to treat it even as a branch of the subject, since the questions raised touch at the core of the discipline itself.

But what is now generally thought of as development economics has a much more recent lineage, and is typically traced to the second half of the twentieth century, indeed, to the immediate postwar period of the 1950s and 1960s when there was a flowering of economic literature relating to both development and underdevelopment. Some of this found its inspiration from the planning literature of the Soviet Union in the interwar period, while others focused on the systemic tendencies in global capitalism that generated inequality and ensure lack of development in some countries, as reflected in “structuralist” analysis. Others retained the fundamentals of the mainstream approach even while altering some of the assumptions. Thus, the economic dualism depicted by Arthur Lewis, the co-ordination failures inherent in less developed economies described by Rosenstein-Rodan, the efficacy of unbalanced “big push” strategies for industrialisation advocated by Albert Hirschman, all in a sense dealt with development policy as a response to the market failures which were specific to latecomers.

All these diverse approaches shared the common perspective that development is not about simply reducing deprivation, but essentially about transformation – structural, institutional and normative – in ways that add to a country’s wealth creating potential, ensuring the gains are widely shared and extending the possibilities for future generations. For most developing countries, that still meant building industrial capacity, providing secure livelihoods for rapidly growing urban populations, guaranteeing food security and providing other basic needs, among other features. This in turn meant that the critical issues related to the nature of growth: the extent to which it generates structural changes in the economy that are associated with increases in the aggregate productivity of labour; the extent to which it generates productive employment for the labour force; the extent to which it ensures that asset and income distribution changes (possibly through redistributive policies) allow the benefits of growth to reach the poor; the extent to which the process increases the access of the population to basic goods and services that affect the quality of life and human poverty.

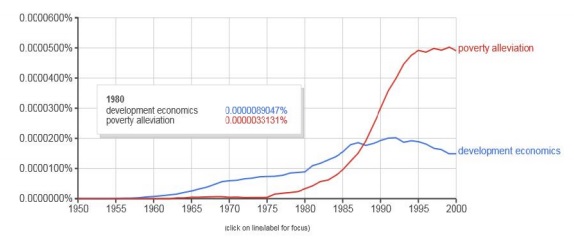

But sometime in the 1980s, all this discussion receded into the background and development economics, even of the mainstream variety, suffered a fate similar to Keynesian economics in developed countries, of being first reviled, then ignored, and finally forgotten. Its place was taken by a focus on “poverty alleviation”, as beautifully captured by 2 this Google Ngram, which quantifies the proportion of instances that these phrases have occurred in a corpus of books over the years.

Figure 1: Ngram for “development economics” and “poverty alleviation” 1950-2000.

This shift in emphasis, and the associated decline of development economics, reflected the perception which had become increasingly widespread within the mainstream economics profession: that all answers to basic economic queries for all types of countries – developed, developing and underdeveloped – could come from the same neoclassical analytical framework which privileged the market mechanism.

The associated focus on poverty alleviation, in what could be called the global “development industry” involves a much sharper focus on the micro, on the miniature as a useful and relevant representation of the larger reality. It is very much a product of the intellectual ethos prevailing in the academic centres of the North – almost all of the practitioners, whatever be their country of origin, actually live and work in these places. Therefore it is a reflection of a deep internalisation of the basic axioms of mainstream North Atlantic economic thinking, especially in terms of the dominance of the neoliberal marketist paradigm.

Some underlying principles of this approach are worth noting since they are rarely explicitly stated. This approach remains firmly entrenched in the methodological individualism that characterises all mainstream economics today. The models tend to be based on the notion that prices and quantities are simultaneously determined through the market mechanism, with relative prices being the crucial factors determining resource allocation as well as the level and composition of output. This holds whether the focus of attention is the pattern of shareholding tenancy or semiformal rural credit markets or a developing economy engaging in international trade.

This literature also posits a basic symmetry not only between supply and demand, but also between factors of production. Thus, the returns on factors – land, labour, capital – are seen as determined along the same lines as the prices of commodities, through simple interaction of demand and supply. Where institutional determinants are acknowledged, they are seen as unwelcome messing about with market functioning, and “government failures” tend to be given wide publicity. An implicit underlying assumption in much of the literature remains that of full employment or at the very most underemployment rather than open unemployment. Further, while externalities are recognised, they are sought to be incorporated into more tractable models, thereby reducing the complexity of their effects. Similarly, while market failures are admitted, the policy interventions proposed or discussed are typically partial equilibrium attempts to insert incentives/disincentives into the market mechanism, with the objective of promoting “efficiency”. And even the basic fact of uneven development tends to be translated into models of “dualism”, which in turn also implies less attention to the differentiation internal to sectors and the patterns of interaction of different groups or classes within and across sectors.

Finally, even when there is a growing acceptance that “history matters”, this is typically reduced to certain simple and modelable statements. Thus, a standard way in the literature of dealing with the effects of history is in the form of complementarities, along the lines made famous by the example of the QWERTY typing keyboard. Other common ways of incorporating history are through inserting “social norms” as a variable, or analysing the effects of the “status quo” in creating inertia with respect to policy changes.

As a result, particular micro features of developing economies tend to be seen as “exotica” in terms of prevalent economic institutions in developing countries, and are then sought to be explained along the lines of methodological individualism, albeit with some cultural nuances. This can be described as a “National Geographic” view of the broader process of development, whereby snapshots of particular institutions or economic activities are taken, the difference from the “norm” of developed capitalism is highlighted and then these are sought to be explained using the same basic analytical tools developed for the “norm”. The means whereby these economies or institutions can then become less different, or more like the developed market ideal (which of course does not exist in reality either), then becomes the focus of the policy proposals emanating from such analyses.

As a result, those who in earlier periods would have been studying development as structural transformation now focus instead on the more limited issue of poverty alleviation. This idea reached its apotheosis in the Millennium Development Goals, and their newly anointed successor, the Sustainable Development Goals, which effectively are directed towards ameliorating the conditions of those defined as poor, rather than transforming the economies in which they live. Even here, the focus is on specific interventions – micro solutions that are seen to work in particular cases – and considering how they can be modified and scaled up. So the global development industry has kept searching for magic silver bullets for poverty alleviation. Over the past decades the fads around supposed panaceas have included successively: freeing markets and getting rid of government controls; recognising the “property rights” to informal settlements of slum dwellers; microfinance; and most recently, cash transfers.

It is interesting that even the focus on poverty alleviation takes a very limited view of what poverty is or how it is generated. Essentially, this is an approach that somehow abstracts from all the basic economic processes and systemic features that determine poverty. So ‘class’ tends to be absent from the discussion, or included only in the form of ‘social discrimination’, with the economic content being effectively wiped out. The poor are not defined by their lack of assets – which would then necessarily draw attention to the concentration of assets somewhere else in the same society – but by lack of monetary income or various other dimensions (such as poor nutrition, bad housing and inferior access to utilities and basic social services, etc.) that are actually symptomatic of their lack of assets. Similarly they are not defined by their economic position or occupation, such as being workers engaged in low paying occupations or unable to find paid jobs or having to find some livelihood in fragile ecologies where survival is fraught with difficulty.

Macroeconomic processes are entirely ignored: patterns of trade and economic activity that determine levels of employment and its distribution and the viability of particular activities, or fiscal policies that determine the extent to which essential public services like sanitation, health and education will be provided, or investment policies that determine the kind of physical infrastructure available and therefore the backwardness of a particular region, or financial policies that create boom and bust volatility in various markets. No link is even hinted at between the enrichment of some and the impoverishment of others, as if the rich and the poor somehow inhabit different social worlds with no economic interdependence at all, and that the rich do not rely upon the labour of the poor. This shuttered vision is particularly evident in the neglect of the international dimension in such analyses, and of the way in which global economic processes and rules impinge on the ability of states in less developed countries to even attempt economic diversification and fulfilment of the social and economic rights of their citizens.

These silences enable a rather two-dimensional view of the poor, who are given the dignity of being treated as subjects with independent decision-making power, but apparently inhabiting a world in which their poverty is unrelated to a wider social, political and economic context, but is more a result of their own particular circumstance and their own often flawed judgements. Since these larger issues are not addressed at all, the only dilemma posed for policy practitioners is of which particular poverty alleviation scheme to choose and how to implement it. For making such decisions, the newest research instrument of choice is that of the “randomised control trial” (RCT) especially as developed by the MIT Jameel Poverty Action Lab and similar institutions. Yet the problems with the widespread use of RCTs in this manner extend beyond the fact that they completely ignore the broader macro processes: quite apart from the statistical problems associated with RCTs as predictors of behaviour or outcomes, there is the simplistic and mechanical belief that what has “worked” in one context can be easily defined and can work in another quite different context.

Rescuing development economics from the miasma created by the discourse on poverty alleviation would require recognising that economic outcomes reflect social and historical factors, the level and nature of institutional development, relative class and power configurations; and that the processes of production and distribution inevitably involve the clash of class interests along with the interaction of social, historical and institutional factors. Since the process of development is an evolutionary one in which there is a continuous interplay of various forces which determine actual outcomes, attempts at poverty alleviation or elimination that do not recognize this are bound to fail.

Originally published in the Frontline.