by Fabius Maximus, FabiusMaximus.com

by Fabius Maximus, FabiusMaximus.com

Summary: One fascinating aspect of globalization is reading descriptions of social dynamics in China or Pakistan, and realizing that this applies as well to America. It is one world. That’s good news, giving us a wider range of solutions to learn from — and even borrow. Also, seeing this commonality helps disprove our delusion of exceptionalism. Today we look at one example: the rural – urban culture wars.

From the opening of Hadji Murat, Tolstoy’s last novel (1917); pdf here:

I gathered myself a large nosegay and was going home when I noticed in a ditch, in full bloom, a beautiful thistle plant of the crimson variety … Thinking to pick this thistle and put it in the center of my nosegay, I climbed down into the ditch, and … set to work to pluck the flower.

But this proved a very difficult task. Not only did the stalk prick on every side — even through the handkerchief I wrapped around my hand — but it was so tough that I had to struggle with it for nearly 5 minutes, breaking the fibers one by one; and when I had at last plucked it, the stalk was all frayed and the flower itself no longer seemed so fresh and beautiful. Moreover, owing to a coarseness and stiffness, it did not seem in place among the delicate blossoms of my nosegay.

I threw it away feeling sorry to have vainly destroyed a flower that looked beautiful in its proper place. “But what energy and tenacity! With what determination it defended itself, and how dearly it sold its life!”

Here is an excerpt from an essential article to read about our mad Long War, with insights for both US domestic affairs and our foreign policy: “Terror: The Hidden Source“, Malise Ruthven, New York Review of Books, 24 October 2013 — A review of The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam by Akbar Ahmed.

Rather than exploiting the denizens of “remote tribal regions” as Obama’s speech proclaimed, the terrorist activities associated with al-Qaeda and its affiliates are actively engaging the responses of tribal peoples (the thistles of Tolstoy’s metaphor) whose cultures are facing destruction from the forces of modern society — including national governments — currently led by the United States.

In this, as in numerous other settings, Ahmed puts his finger on the crucial linkage connecting the localisms of tribal conflicts with the broader Islamic notion of global jihad. His theme is not some vaguely defined “clash of civilizations” but rather the clash between metropolitan centers and rural peripheries that is internal to all modern civilizations—whether these be Islamic, Western, Russian, or Chinese. He provides numerous examples to show that the “thistles” of Tolstoy’s metaphor are to be found in a wide variety of regions, including Somalia, Yemen, Afghanistan, Kashmir, and Pakistan’s northwest frontier, as well as Berber North Africa, Nigeria, and Aceh in Indonesia.

Ahmed produces an impressive body of data to support his argument that tribal systems are coming under attack everywhere from the forces of the modernizing state. With regard to Waziristan, for example, where he served as a Pakistani political agent before entering academic life, he finds that

every aspect of life — religious… and political leadership, customs, and codes — is in danger of being turned upside down. The particles that formed the kaleidoscope of history and remained stationary for so long have now been shaken about in bewildering patterns, with no telling when and how they will settle into some recognizable forms.

Same analysis, but applied to America

This analysis applies quite well to the culture wars in America, to a large extent a result of the widening gulf between rural and urban populations. Tweaked, Ruthven’s article could read as an article about the Tea Party: a vain attempt to retain power by a cultural besieged and fading group..

One society with two cultures: not a new problem

(a) Rural culture is dying. The culture wars are to a large extent fought across rural – urban boundaries, and the conservatives are losing. Gay marriage being the latest battle. Hunting is becoming less popular.

(b) Many rural communities are dying. Literally, as their residents age and their young move to cities. From “Population Losses Mount in U.S. Rural Areas“, Mark Mather, Population Reference Bureau, March 2008:

Many rural communities, particularly in the Midwest, have been losing population for decades and are on the brink of extinction.

The Economic Research Service at the U.S. Department of Agriculture attributes population loss in rural areas to declines in farming and other rural industries, high poverty rates, lack of services, and — in some areas — a lack of natural amenities such as warm winters, forests, or lakes. The fact that most out-migrants are of reproductive age compounds the problem, because it means that fewer babies are being born to replace the aging population. Of the 1,346 counties that shrank in population between 2000 and 2007, 85% are located outside of metropolitan areas, and 59% rely heavily on farming, manufacturing, or mining.

This trend has accelerated since 2008 per an analysis of US Census Bureau data through July 2012 by the Department of Agriculture.

(c) Partisan divisions are increasingly urban-rural instead of regional

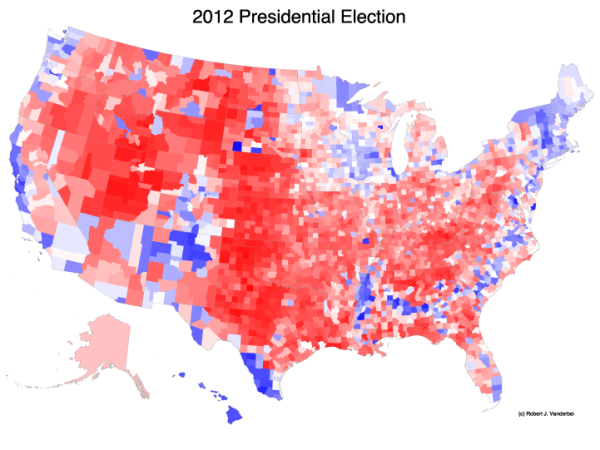

See “Red State, Blue City: How the Urban-Rural Divide Is Splitting America“, Josh Kron, The Atlantic, 30 November 2012. Also see these maps of 2012 election results by county from website of Robert Vanderbai (Prof Operations Research, Princeton):

From website of Professor Robert Vanderbai, Princeton

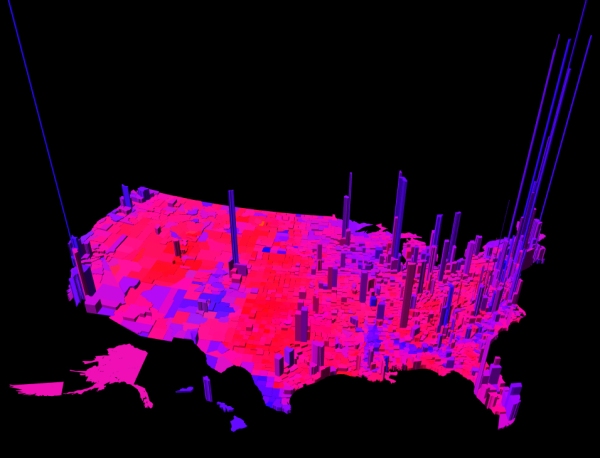

Same data, a more dramatic perspective:

From website of Professor Robert Vanderbai, Princeton.

For More Information

About motives of jihadists:

- How I learned to stop worrying and love Fourth Generation War. We can win at this game.

- We are the attackers in the Clash of Civilizations. We’re winning.

- Handicapping the clash of civilizations: bet on America to win.

The way many rural conservatives see the world