by Federal Reserve Governor Elizabeth A. Duke, At the Housing Policy Executive Council, Washington, D.C.

Since joining the Board in 2008 amid a crisis centered on mortgage lending, I have focused much of my attention on housing and mortgage markets, issues surrounding foreclosures, and neighborhood stabilization. In March of this year, I laid out my thoughts on current conditions in the housing and mortgage markets in a speech to the Mortgage Bankers Association.[1] Today I will summarize and update that information with a focus on mortgage credit conditions. Before I proceed, I should note that the views I express are my own and not necessarily those of my colleagues on the Board of Governors or the Federal Open Market Committee.

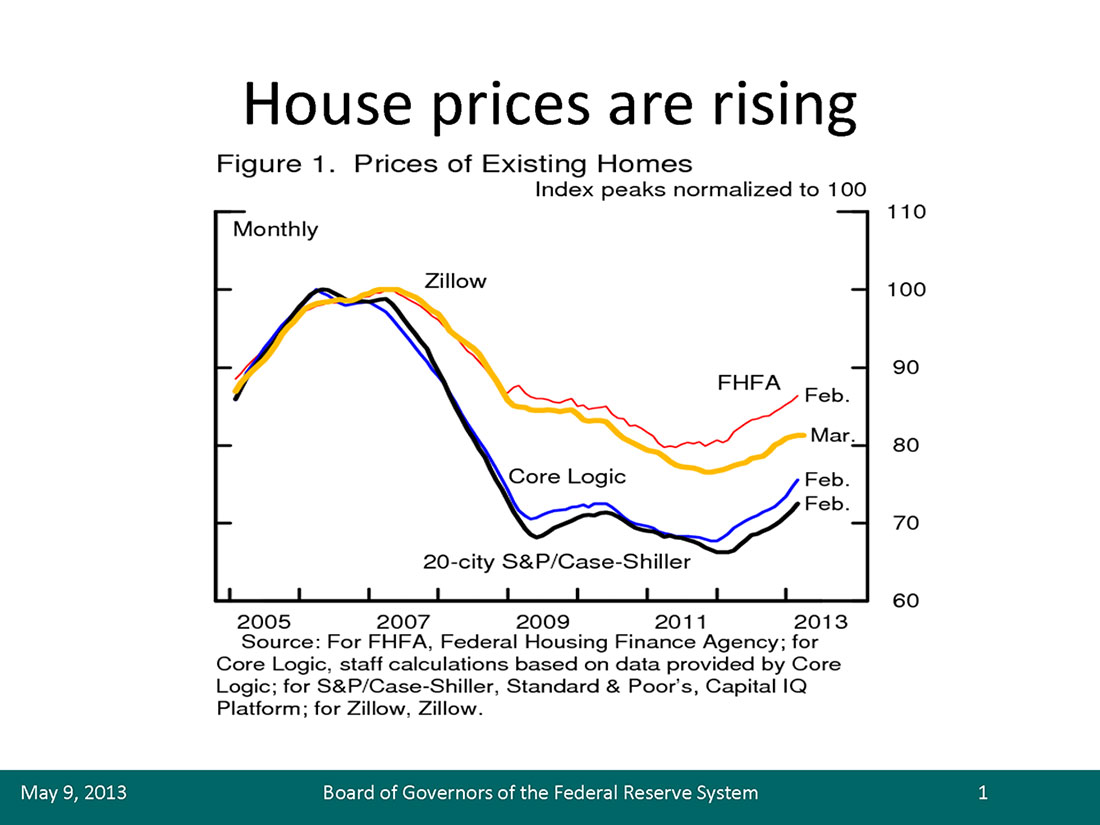

A sustained recovery in the housing market appears to be under way. House prices, as measured by a variety of national indexes, have risen 6 to 11 percent since the beginning of 2012[2].

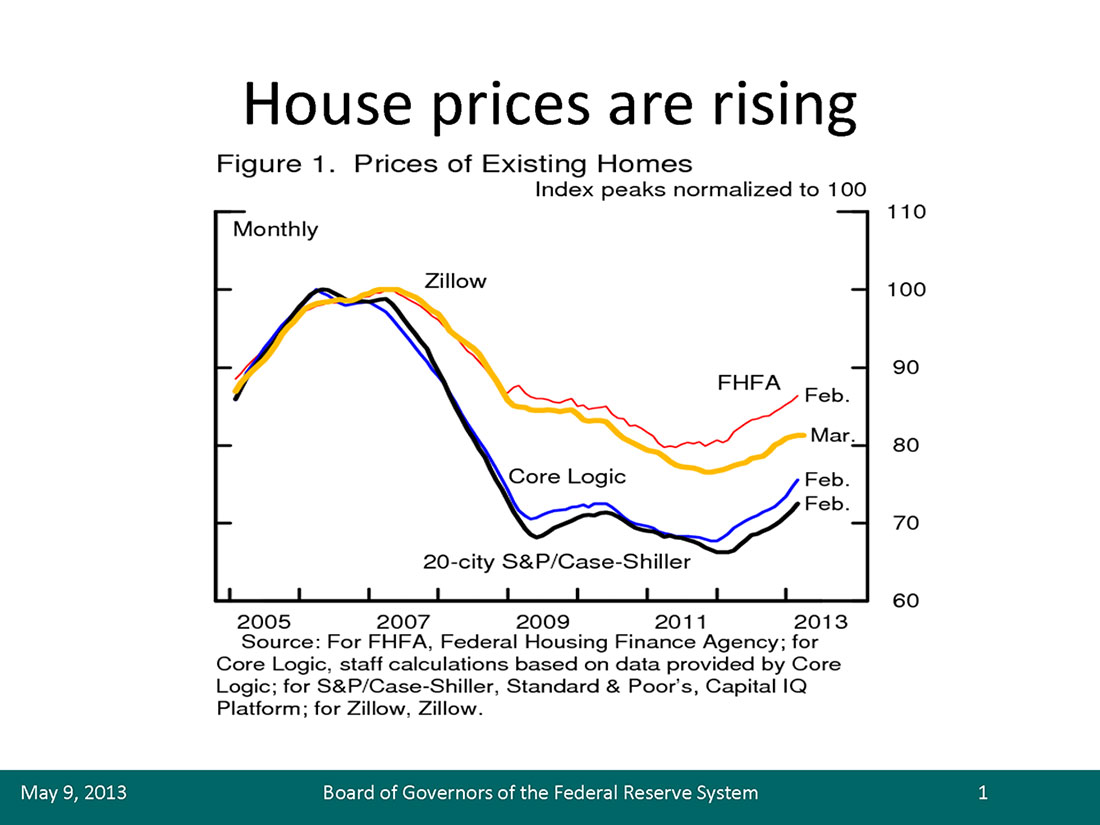

The recovery of house prices has been broad based geographically, with 90 percent of local markets having experienced price gains over the year ending in February. Also since the beginning of 2012, housing starts and permits have risen by nearly 30 percent, while new and existing home sales have also seen double-digit growth rates.

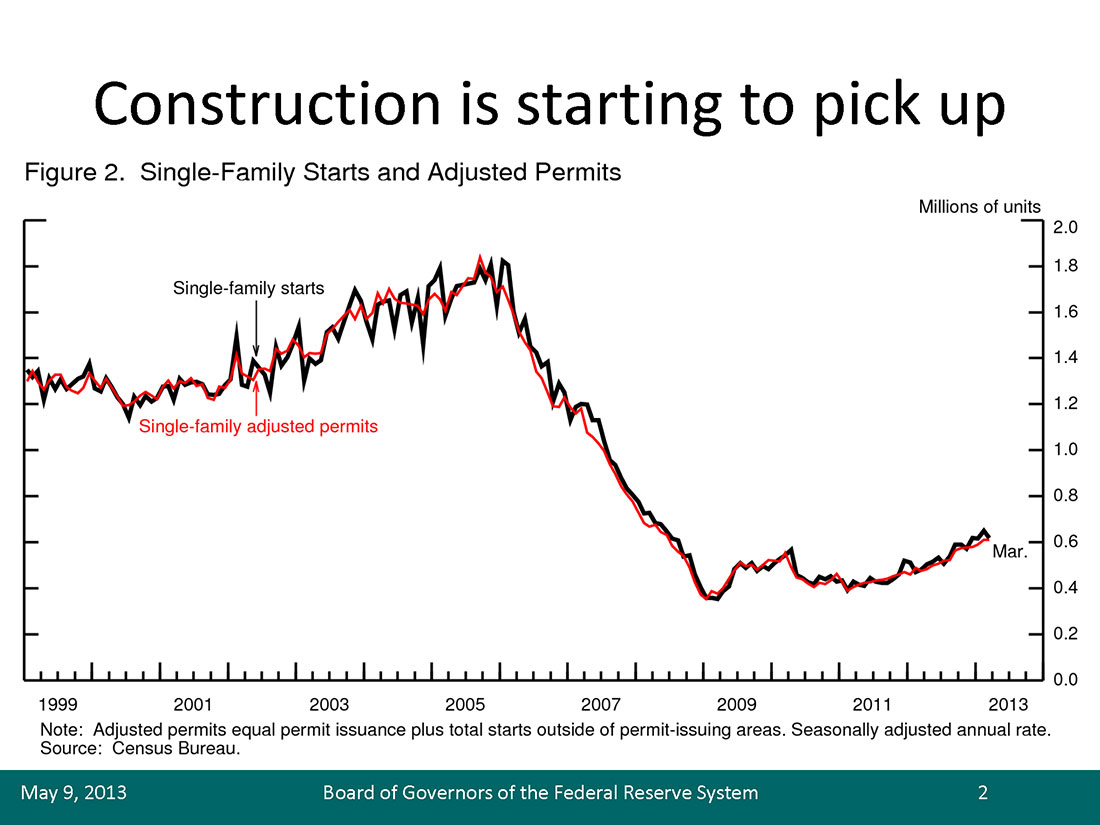

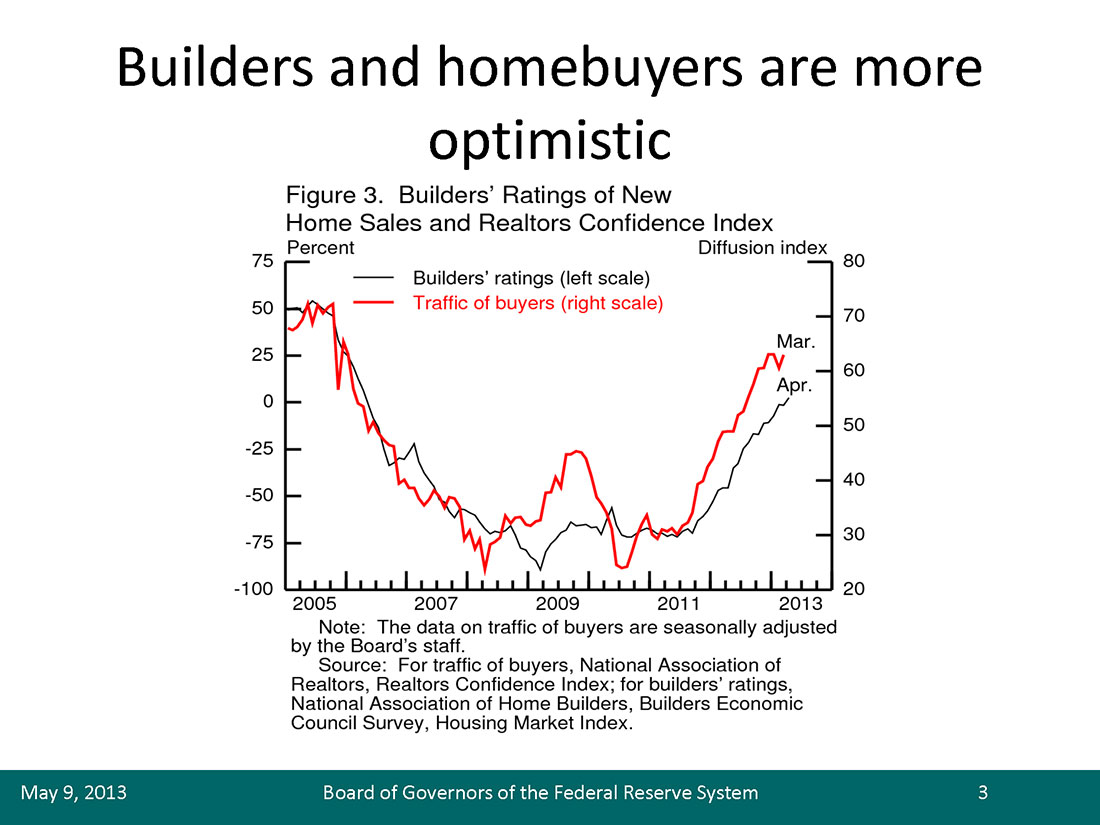

Homebuilder sentiment has improved notably, and real estate agents report stronger traffic of people shopping for homes [3].

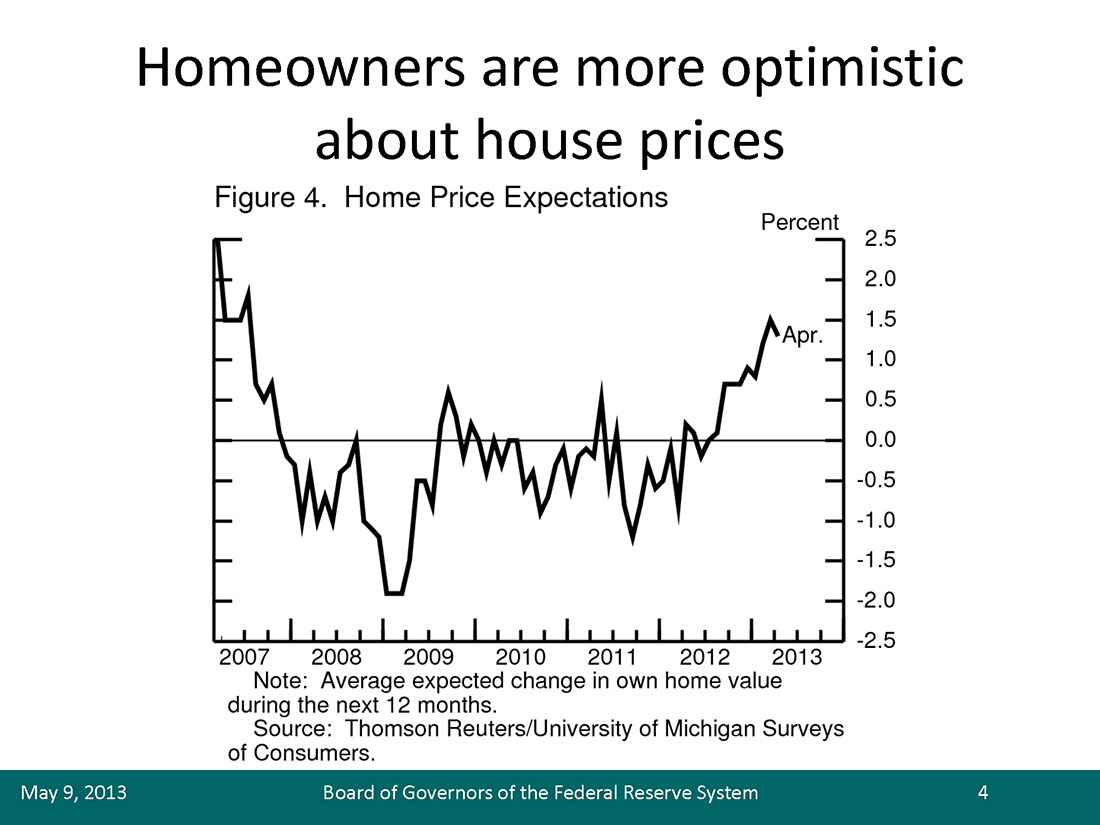

In national surveys, households report that low interest rates and house prices make it a good time to buy a home; they also appear more certain that house price gains will continue[4].

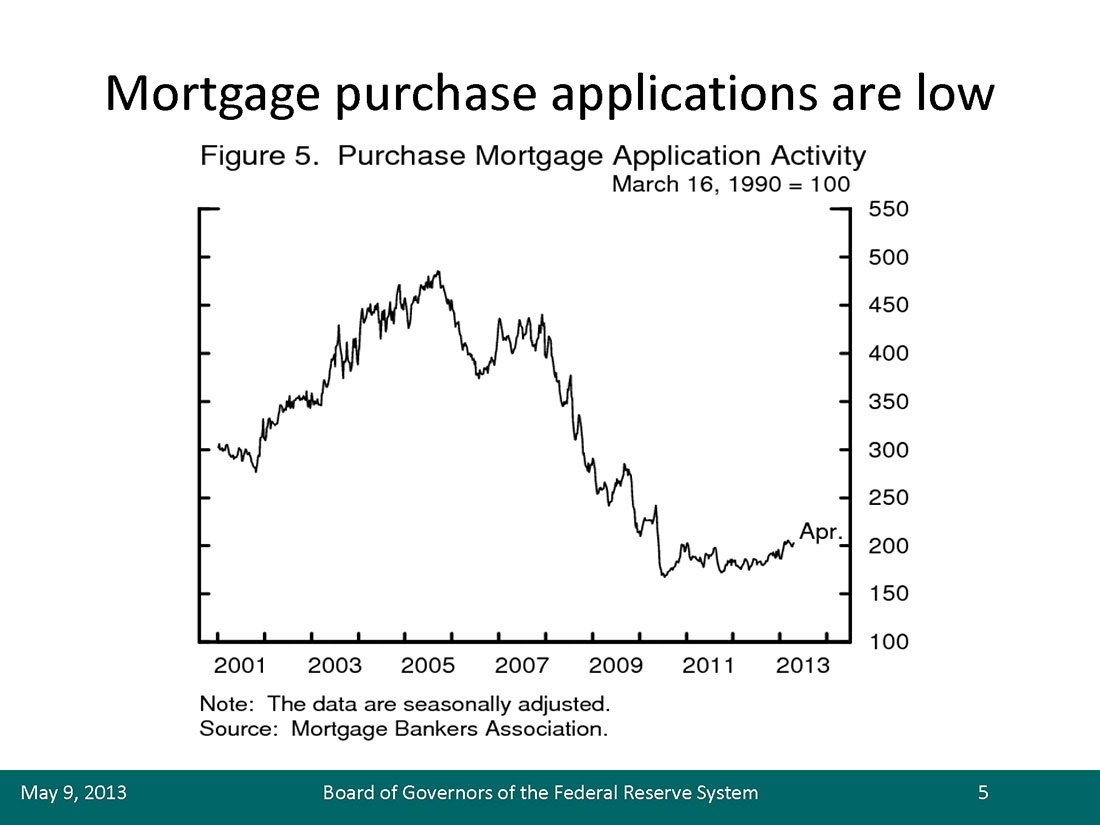

Despite the recent gains, the level of housing market activity remains low. Existing home sales are currently at levels in line with those seen in the late 1990s, while single-family starts and permits are at levels commensurate with the early 1990s. And applications for home-purchase mortgages, as measured by the Mortgage Bankers Association index, were at a level in line with that of the mid-1990s.

The subdued level of mortgage purchase originations is particularly striking given the record low mortgage rates that have prevailed in recent years.

The drop in originations has been most pronounced among borrowers with lower credit scores. For example, between 2007 and 2012, originations of prime purchase mortgages fell about 30 percent for borrowers with credit scores greater than 780, compared with a drop of about 90 percent for borrowers with credit scores between 620 and 680[5].

Originations are virtually nonexistent for borrowers with credit scores below 620. The distribution of credit scores in these purchase origination data tells the same story in a different way: The median credit score on these originations rose from 730 in 2007 to 770 in 2013, whereas scores for mortgages at the 10th percentile rose from 640 to 690.

Many borrowers who have faced difficulty in obtaining prime mortgages have turned to mortgages insured or guaranteed by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), or the Rural Housing Service (RHS). Data collected under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act indicate that the share of purchase mortgages guaranteed or insured by the FHA, the VA, or the RHS rose from 5 percent in 2006 to more than 40 percent in 2011 [6].

But here, too, loan originations appear to have contracted for borrowers with low credit scores. The median credit score on FHA purchase originations increased from 625 in 2007 to 690 in 2013, while the 10th percentile has increased from 550 to 650 [7].

Part of the contraction in loan originations to households with lower credit scores may reflect weak demand among these potential homebuyers. Although we have little data on this point, it may be the case that such households suffered disproportionately from the sharp rise in unemployment during the recession and thus have not been in a financial position to purchase a home.

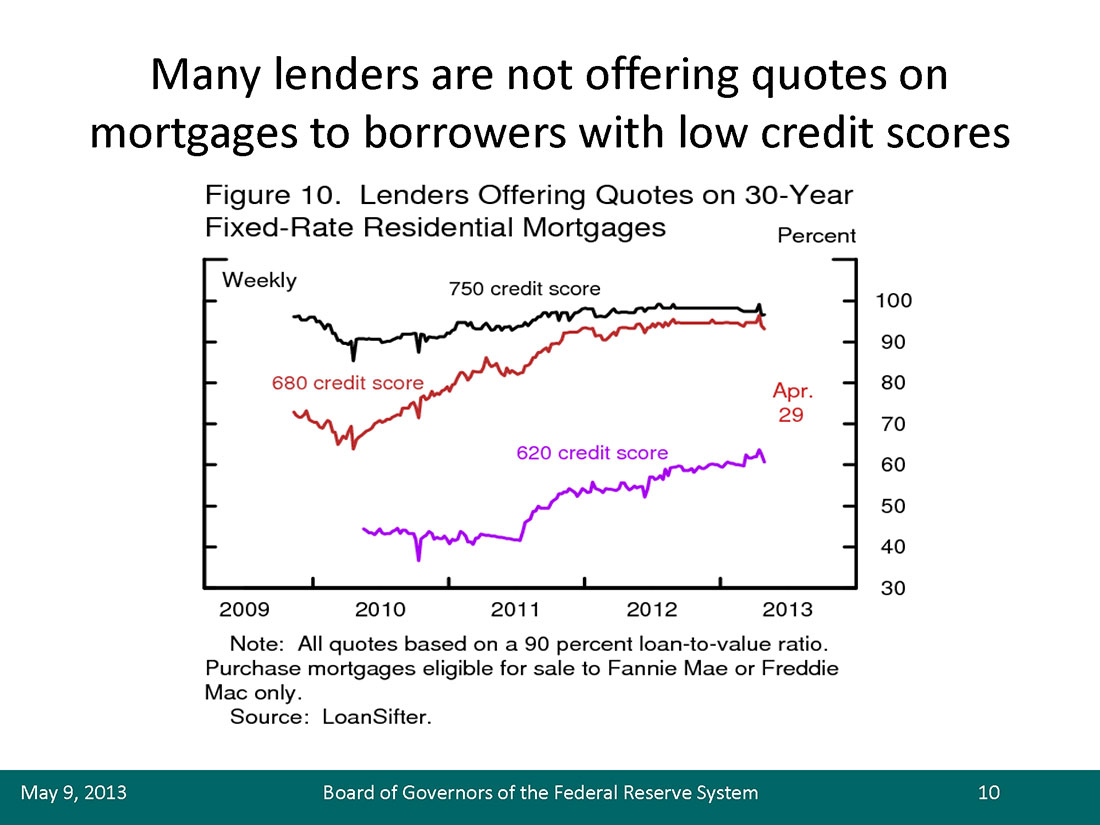

There is evidence that tight mortgage lending conditions may also be a factor in the contraction in originations. Data from lender rate quotes suggest that almost all lenders have been offering quotes (through the daily “rate sheets” provided to mortgage brokers) on mortgages eligible for sale to the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) to borrowers with credit scores of 750 over the past two years[8]. Most lenders have been willing to offer quotes to borrowers with credit scores of 680 as well. Fewer than two-thirds of lenders, though, are willing to extend mortgage offers to consumers with credit scores of 620 [9].

And this statistic may overstate the availability of credit to borrowers with lower credit scores: The rates on many of these offers might be unattractive, and borrowers whose credit scores indicate eligibility may not meet other aspects of the underwriting criteria.

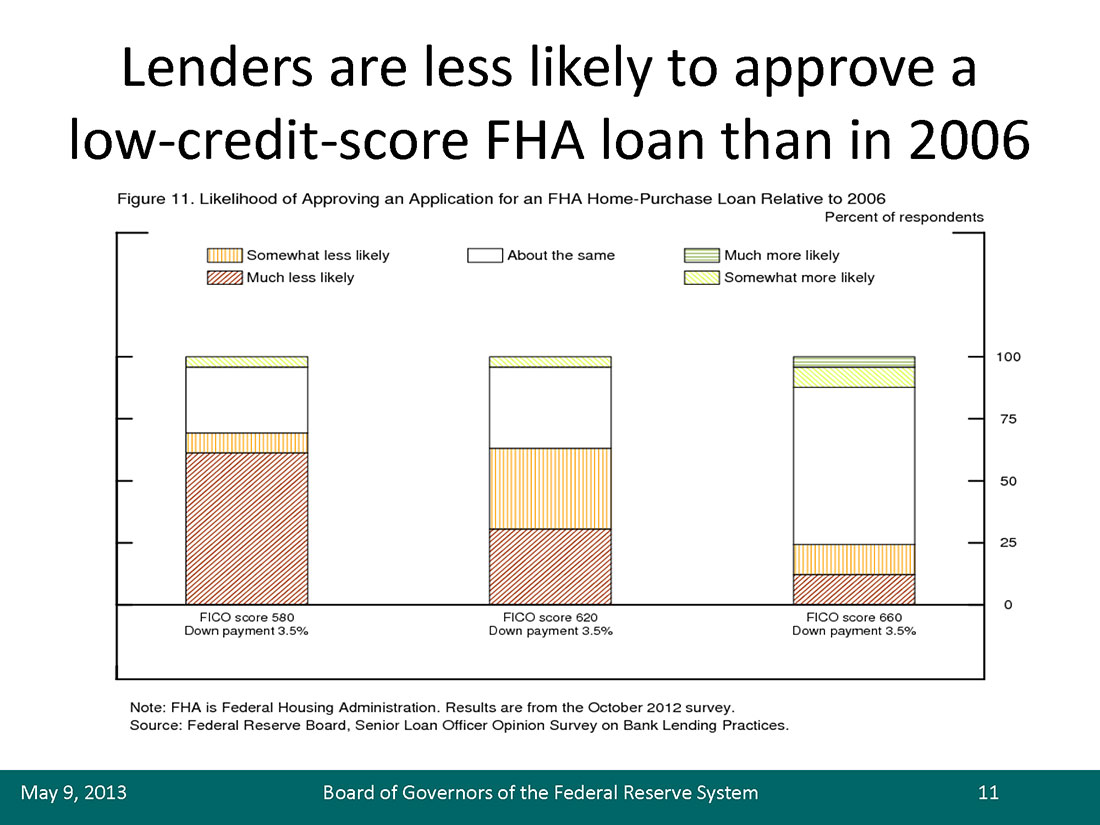

Tight credit conditions also appear to be part of the story for FHA-insured loans. In the Federal Reserve’s October 2012 Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices (SLOOS), one-half to two-thirds of respondents indicated that they were less likely than in 2006 to originate an FHA loan to a borrower with a credit score of 580 or 620.

Standards have tightened a bit further since: In the April 2013 SLOOS, about 30 percent of lenders reported that they were less likely than a year ago to originate FHA mortgages to borrowers with a credit score of 580 or 620 [10].

The April SLOOS offers some clues about why mortgage credit is so tight for borrowers with lower credit scores. Banks participating in the survey identified a familiar assortment of factors as damping their willingness to extend any type of loan to these borrowers: the risk that lenders will be required to repurchase defaulted loans from the GSEs (“putback” risk), the outlook for house prices and economic activity, capacity constraints, the risk-adjusted opportunity cost of such loans, servicing costs, balance sheet or warehousing capacity, guarantee fees charged by the GSEs, borrowers’ ability to obtain private mortgage insurance or second liens, and investor appetite for private-label mortgage securitizations. Respondents appeared to put particular weight on GSE putbacks, the economic outlook, and the risk-adjusted opportunity cost. In addition, several large banks cited capacity constraints and borrowers’ difficulties in obtaining private mortgage insurance or second liens as at least somewhat important factors in restraining their willingness to approve such loans.

Over time, some of these factors should exert less of a drag on mortgage credit availability. For example, as the economic and housing market recovery continues, lenders should gain confidence that mortgage loans will perform well, and they should expand their lending accordingly.

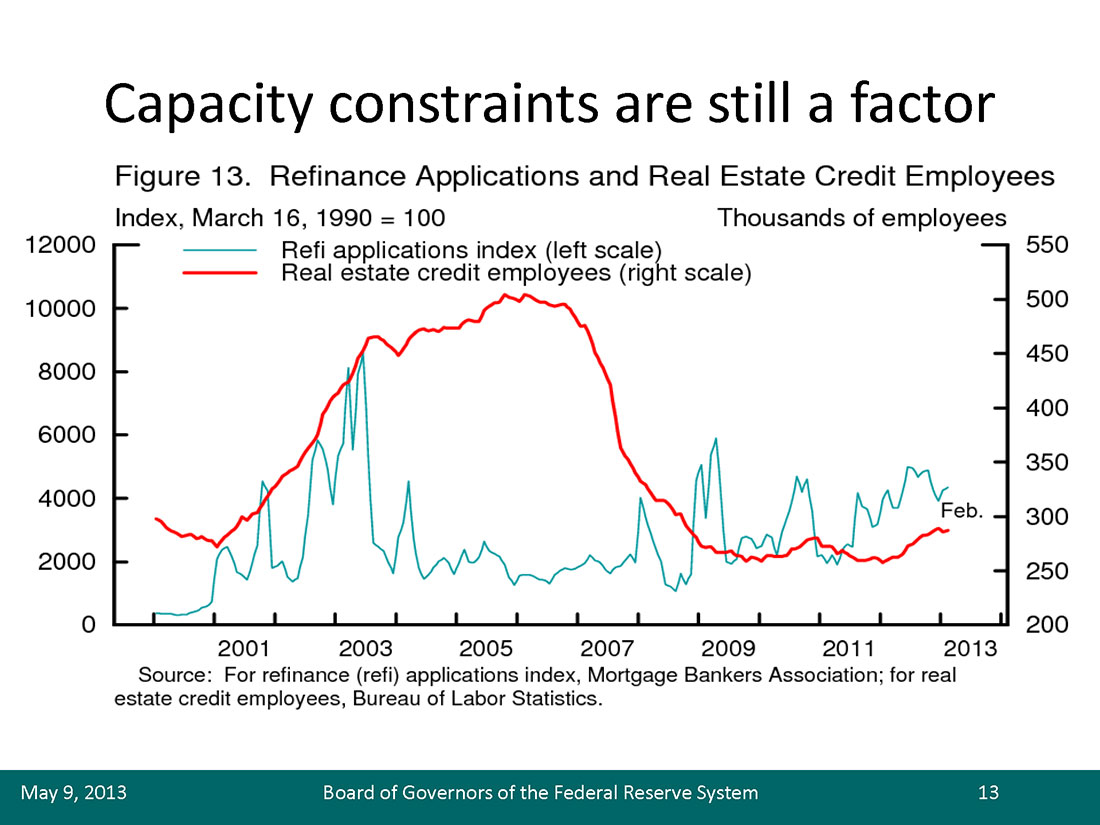

Capacity constraints will likely also ease. Refinancing applications have expanded much more over the past year and a half than lenders’ ability to process these loans. For example, one measure of capacity constraints–the number of real estate credit employees–has only edged up over this period.

When capacity constraints are binding, lenders may prioritize the processing of easier-to-complete or more profitable loan applications. Indeed, preliminary research by the Board’s staff suggests that the increase in the refinance workload during the past 18 months appears to have been associated with a 25 to 35 percent decrease in purchase originations among borrowers with credit scores between 620 and 680 and a 10 to 15 percent decrease among borrowers with credit scores between 680 and 710 [11]. Any such crowding-out effect should start to unwind as the current refinancing boom decelerates.

Other factors holding back mortgage credit, however, may be slower to unwind. As the SLOOS results indicate, lenders remain concerned about putback risk. The ability to hold lenders accountable for poorly underwritten loans is a significant protection for taxpayers. However, if lenders are unsure about the conditions under which they will be required to repurchase loans sold to the GSEs, they may shy away from originating loans to borrowers whose risk profiles indicate a higher likelihood of default. The Federal Housing Finance Agency launched an important initiative last year to clarify the liabilities associated with representations and warranties, but, so far, putback risk appears to still weigh on the mortgage market.

Mortgage servicing standards, particularly for delinquent loans, are more stringent than in the past due to settlement actions and consent orders. Servicing rules recently released by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) will extend many of these standards to all lenders[12]. These standards remedy past abuses and provide important protections to borrowers, but also increase the cost of servicing nonperforming loans. This issue is compounded by current servicing compensation arrangements under which servicers receive the same fee for the routine processing of current loans as they do for the more expensive processing of delinquent loans. This model–especially in conjunction with higher default-servicing costs–gives lenders an incentive to avoid originating loans to borrowers who are more likely to default. A change to servicer compensation models for delinquent loans could alleviate some of these concerns.

Government regulations will also affect the cost of mortgage credit. In January, the CFPB released rules, in addition to those for servicing standards, on ability-to-repay requirements, the definition of a qualified mortgage (QM), and loan originator compensation[13]. The Federal Reserve and other agencies are in the process of moving forward on proposed rulemakings that would implement revised regulatory capital requirements and the requirements for risk retention mandated by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, which include an exemption for mortgages that meet the definition of qualified residential mortgages (QRM).

As the regulatory capital and risk retention requirements are still under deliberation, I won’t comment on these regulations today. However, I will share a few thoughts on the possible effects of the QM rulemaking on access to credit.

As background, the QM rule is part of a larger ability-to-repay rulemaking that requires lenders to make a reasonable and good faith determination that the borrower can repay the loan. The rulemaking addresses the lax underwriting practices that flourished during the housing boom by setting minimum underwriting standards and by providing borrowers with protections against lending abuses. In particular, borrowers can sue the lender for violations of the ability-to-repay rules and claim monetary damages. If the original lender sells or securitizes the loan, the borrower can claim these damages at any time in a foreclosure action taken by the lender or any assignee. If the mortgage meets the QM standard, however, the lender receives greater protection from such potential lawsuits because it is presumed that the borrower had the ability to repay the loan.

Loans that fall outside the QM standard may be more costly to originate than loans that meet the standard for at least four reasons, all else being equal. The first reason is the possible increase in foreclosure losses and litigation costs. Although these costs, in the aggregate, are expected to be small, their full extent will not be known until the courts settle any ability-to-repay suits that may be brought forward [14]. The second reason is that mortgages that do not meet the QM definition will also not qualify as QRMs, so lenders will be required to hold some of the risk if these loans are securitized [15]. The third reason is that loan originators will have better information than investors on the quality of the underwriting decision. Investors may demand a premium to compensate them for the concern that originators might sell them the loans most vulnerable to ability-to-repay lawsuits. The fourth reason is that the non-QM market, at least initially, may be small and illiquid, which would increase the cost of these loans.

The higher costs associated with non-QM loans should have very little effect on access to credit in the near term because almost all current mortgage originations meet the QM standard. The vast majority of current originations are eligible to be purchased, insured, or guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the FHA, the VA, or the RHS. These loans are classified as QMs under the rule [16]. The small proportion of mortgages originated at present outside of these programs, for the most part, are being underwritten to tight standards consistent with the QM definition.

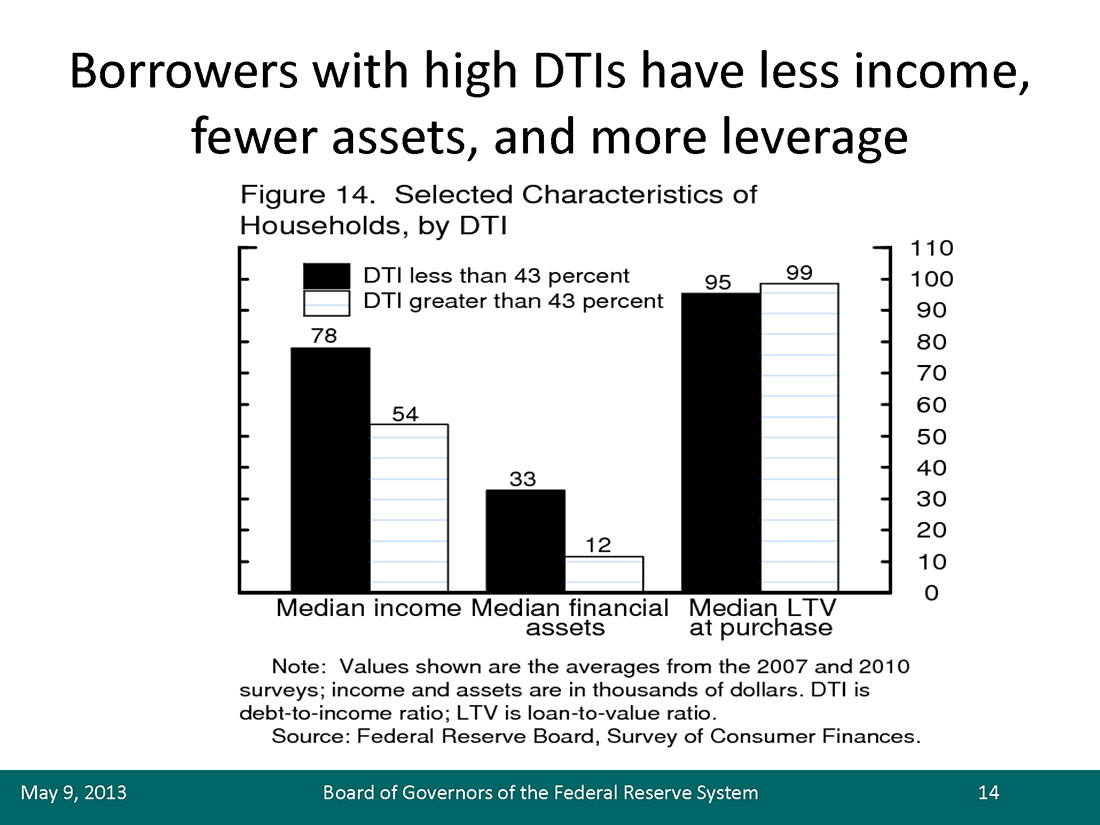

As lender risk appetite increases and private capital returns to the mortgage market, a larger non-QM market should start to develop. Two aspects of the QM rule, though, may make this market slow to develop for borrowers with lower credit scores. First, the QM requirement that borrower payments on all debts and some recurring obligations must be 43 percent or less of borrower income may disproportionately affect less-advantaged borrowers[17]. Board staff tabulations based on the Survey of Consumer Finances indicate that such households tend to have lower incomes, fewer financial assets, and higher mortgage loan-to-value ratios than households with lower payment ratios [18].

Second, the QM definition affects lenders’ ability to charge for the risks of originating loans to borrowers who are more likely to default. For example, lenders may in general compensate for this risk by charging a higher interest rate on the loan. However, if lenders originate a first-lien QM with an annual percentage rate that is 150 basis points or more above the rate available to the highest-quality borrowers, lenders receive less protection against lawsuits claiming violation of the ability-to-repay and QM rules[19]. Lenders who prefer to price for risk through points and fees face the constraint that points and fees on a QM loan may not exceed 3 percent of the loan amount, with higher caps available for loans smaller than $100,000. The extent to which these rules regarding rates, points, and fees will damp lender willingness to originate mortgages to borrowers with lower credit scores is still unclear.

To summarize, the housing market is improving, but mortgage credit conditions remain quite tight for borrowers with lower credit scores. And the path to easier credit conditions is somewhat murky. Some of the forces damping mortgage credit availability, such as capacity constraints and concerns about economic conditions or house prices, are likely to unwind through normal cyclical forces. However, resolution of lender concerns about putback risk or servicing cost seems less clear. These concerns could be reduced by policy changes. For example, the structure of liability for representations and warrantees could be modified. Or servicing compensation could be changed to provide higher compensation for the servicing of delinquent loans. Or lenders might find ways to reduce their exposure to putback risk or servicing cost by strengthening origination and servicing platforms. New mortgage regulations will provide important protections to borrowers but may also lead to a permanent increase in the cost of originating loans to borrowers with lower credit scores. It will be difficult to determine the ultimate effect of the regulatory changes until they have all been finally defined and lenders gain familiarity with them.

The implications for the housing market are also murky. Borrowers with lower credit scores have typically represented a significant segment of first-time homebuyers. For example, in 1999, more than 25 percent of first-time homebuyers had credit scores below 620 compared with fewer than 10 percent in 2012 [20].

Although I expect housing demand to expand along with the economic recovery, if credit is hard to get, much of that demand may be channeled into rental, rather than owner-occupied, housing.

At the Federal Reserve, we continue to foster more-accommodative financial conditions and, in particular, lower mortgage rates through our monetary policy actions. We also continue to monitor mortgage credit conditions and consider the implications of our rulemakings for credit availability. For your part, I urge you to continue to develop new and more sustainable business models for lending to lower-credit-score borrowers that lead to better outcomes for borrowers, communities, and the financial system than we have experienced over the past few years.

1. See Elizabeth A. Duke (2013), “Comments on Housing and Mortgage Markets,” speech delivered at “Mid-Winter Housing Finance Conference,” sponsored by the Mortgage Bankers Association, held in Avon, Colo., March 6-9.

2. House price information is from staff calculations based on data from CoreLogic, Zillow, Standard & Poor’s, and the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

3. More details on homebuilder sentiment are available on the National Association of Home Builders website ![]() . Additional details on real estate agent assessments of market conditions are available at the National Association of Realtors® website

. Additional details on real estate agent assessments of market conditions are available at the National Association of Realtors® website ![]() .

.

4. Household reports are from staff calculations based on results of the Thomson Reuters/University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers ![]() .

.

5. These calculations are based on data provided by McDash Analytics, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Lender Processing Services, Inc. The underlying data are provided by mortgage servicers. These servicers classify loans as “prime,” “subprime,” or “FHA.” Prime loans include those eligible for sale to the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) as well as those with favorable credit characteristics but loan sizes that exceed the GSE guidelines (“jumbo” loans).

6. Staff calculations suggest that the FHA and VA market share dipped a bit in 2012 but remained quite elevated. These calculations are based on data provided by McDash Analytics, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Lender Processing Services, Inc.

7. The shift in the distributions may partly reflect changes in the FHA’s underwriting guidelines. In 2010, the FHA required a minimum credit score of 580 in order to qualify for a loan with a 3.5 percent down payment. In 2013, the FHA required manual underwriting for loans with a credit score less than 620 and a debt-to-income ratio greater than 43 percent. See U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (2010), “FHA Announces Policy Changes to Address Risk and Strengthen Finances,” press release, January 20; and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (2013), “FHA Takes Additional Steps to Bolster Capital Reserves,” press release, January 30.

8. These quotes assume that the borrower supplies a 10 percent down payment.

9. These data series begin in 2009 and 2010, so we cannot compare the current level of rate quotes to those that prevailed before the financial crisis. However, in response to a special question on the Federal Reserve’s April 2012 Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices, nearly 85 percent of lenders reported that they were somewhat or much less likely than in 2006 to originate a mortgage to a borrower with a credit score of 620 and a down payment of 10 percent. This response suggests that credit supply has contracted for such borrowers.

10. The October 2012 and April 2013 surveys are available on the Federal Reserve Board’s website.

11. These estimates are smaller than the estimates in the March 2013 Mortgage Bankers Association speech because capacity constraints appear to have become less severe in recent months (see Duke, “Comments on Housing and Mortgage Markets,” in note 1). These estimates are for the period from February 2011 to February 2013. The March estimates were for the period from October 2010 to October 2012.

12. See CFPB (2013), “2013 Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (Regulation X) and Truth in Lending Act (Regulation Z) Mortgage Servicing Final Rules,” Regulations: Final Rules Issued by the CFPB 2013, webpage, January 17.

13. For more on ability-to-repay requirements and the definition of a QM, see CFPB (2013), “Ability to Repay and Qualified Mortgage Standards under the Truth in Lending Act (Regulation Z),” Regulations: Final Rules Issued by the CFPB 2013, webpage, January 10. For information on loan originator compensation, see CFPB (2013), “Loan Originator Compensation Requirements under the Truth in Lending Act (Regulation Z),” Regulations: Final Rules Issued by the CFPB 2013, webpage, January 20.

14. The CFPB estimates of these costs are available at section VII.E.3.

15. If a mortgage-backed security is collateralized by “qualified residential mortgages,” as defined by federal regulators consistent with section 941 of the Dodd-Frank Act, the securitizer is not required to retain any risk in the securitization transaction. Otherwise, the securitizer must retain an economic interest in the transaction consistent with section 941 and any regulations established thereunder, which may increase the securitizer’s costs. The Dodd-Frank Act requires that Federal regulators set the definition of a QRM to be no broader than the definition of a QM.

16. This provision is slated to end no later than January 2021. The Dodd-Frank Act gives the FHA, the VA, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the RHS the option to write separate QM regulations for their mortgages.

17. Borrowers with debt-to-income (DTI) ratios greater than 43 percent may still be able to obtain QMs if the mortgage is guaranteed by the FHA or eligible for purchase by the GSEs.

18. The tabulation is based on households that purchased a home with mortgage credit in the two years preceding the Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances for 2001, 2004, 2007, and 2010. About 15 percent of borrowers in the 2001, 2004, and 2010 surveys and 25 percent in the 2007 survey had DTIs greater than 43 percent. The 2007 statistic was reported incorrectly in the March 2013 Mortgage Bankers Association speech (see Duke, “Comments on Housing and Mortgage Markets,” in note 1). DTI is measured at the time of the survey, not at the time of the loan origination, and may understate the number of affected households if household finances improve after the purchase of a home.

19. The CFPB has proposed a higher spread threshold for first-lien QMs originated by small creditors and for certain types of balloon mortgages.

20. Staff calculations are based on the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel. First-time homebuyers are measured as consumers who have no record of ever having a mortgage at the end of the second quarter of a given year and opened a mortgage in the third quarter. This estimate includes all types of mortgages but excludes first-time homebuyers who purchased their homes with cash. The credit score was generated from the Equifax 3.0 risk model and measured the credit score as of the end of the second quarter. Consumers without a credit score are excluded from the analysis.