by John Mauldin, Thoughts from the Frontline

“I know the Chinese. I’ve made a lot of money with the Chinese. I understand the Chinese mind.” – Donald Trump, 2011

Back in the olden days (pre-2000 or so), information junkies like me relied on printed newspapers, paper magazines, TV newscasts, and snail-mail newsletters. All these channels still exist, but they can’t begin to compete with the constant stream of data rushing into our tablets and smartphones. And on some days the stream rushes faster.

Last week, for instance, it seemed I couldn’t go five minutes without another story on either (a) China or (b) Donald Trump. For a day or so, I really wondered if someone had planted malware in my browser to make me think all other topics were inconsequential. It was all Trump and China, all day and all night. China has pushed the Fed into second place (for a few days at least) – perhaps we should be grateful that at least something has. Of course, there is the little problem that a bear market might be in the offing. Commodity prices seem to be in the toilet. Global currency markets are throwing up. Isn’t the world supposed to be on vacation in August?

Let’s see if we can find a connecting thought or three among all these topics. Plus, I want to show you how the current market meltdown is being brought to you courtesy of your friendly US Federal Reserve Bank. As our starting point, though, let’s cast an eye at The Donald and Chinese currency manipulation.

Nobody Does Anything

As we all know by now, on Aug. 11 the People’s Bank of China changed the way it manages the renminbi daily trading band against the US dollar. The result was a two-day drop for the RMB and a lot of consternation on trading floors around the world.

Taking questions at an event in Michigan that day, Donald Trump had this to say:

I think you have to do something to rein in China. They devalued their currency today. They’re making it absolutely impossible for the United States to compete, and nobody does anything. China has no respect for President Obama whatsoever, whatsoever.

Well, you have to take strong action. How can we compete? They continuously cut their currency. They devalue their currency. And I have been saying this for years. They have been doing this for years. This isn’t just starting. This was the largest devaluation they have had in two decades. They make it impossible for our businesses, our companies to compete.

They think we’re run by a bunch of idiots. And what’s going on with China is unbelievable, the largest devaluation in two decades. It’s honestly – great question – it’s a disgrace.”

Before you dismiss this as nonsense, remember that it comes from a Wharton School graduate.

Still not impressed? You’re right; it is indeed nonsense. Trump and all those who prattle on about Chinese currency manipulation have the economic comprehension of a parakeet. Is Trump really so clueless?

In one sense, it doesn’t matter. Trump isn’t talking to most of us. He draws an audience of frustrated, mostly middle-class Americans who are still hurting from the Great Recession. They want to blame someone. China is an easy target. So are illegal immigrants and Mexico and other faceless culprits. Furthermore, his audience has legitimate concerns. They are fully aware that both political parties ignore them.

A recent Gallup poll shows that 75% of our country believes there is significant corruption in government. They’re tired of it. They want to try something different. It is telling that a recent Michigan poll of Republican party activists found that 55% would go with either untested non-politicians or Ted Cruz, who is about as much of an outsider as you can find inside the Washington DC Beltway. I find almost nothing attractive about Donald Trump, but significant numbers in both parties have clearly demonstrated that they are looking for real change. Shades of Greece and Syriza’s coming to power, or France and the startling surge by Marine Le Pen’s Front National. The US is beginning to experience what our European friends have been living through the past few years.

Back to Trump and currency manipulation. I could do a sentence-by-sentence analysis of his populist harangue on China, but let’s take the really egregious statement:

How can we compete? They continuously cut their currency. They devalue their currency. And I have been saying this for years. They have been doing this for years. This isn’t just starting. This was the largest devaluation they have had in two decades. They make it impossible for our businesses, our companies to compete.

No, they haven’t. This whole myth that China has purposely kept their currency undervalued needs to be completely excised from the economic discussion. First off, the two largest currency-manipulating central banks currently at work in the world are (in order) the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank. And two to four years ago the hands-down leading manipulator would have been the Federal Reserve of the United States. The leaders/aggressors in the currency wars come and go.

Today, the euro is off over 30% from its highs, as is the Japanese yen. Numerous other currencies are likewise well into double-digit slides. China has moved maybe 3 to 4%. Oh, wow.

Secondly, Donald (and to be fair I should address this to Senators Schumer and Graham, et al., too) the Chinese have not been continuously cutting their currency for years. In fact, if they have manipulated their currency, it was first to make it even stronger when the dollar was falling and then to hold those gains in the face of the steadily rising dollar. Meanwhile the rest of the world (Japan, Europe, Great Britain, Brazil, India, among others) was letting their currencies drift down. The simple fact is that the Chinese currency rose by 20% over the last five years up until a week ago, for reasons we will examine a little later. It is utterly wrong-headed to call a 20% rise over almost 10 years “continuous devaluation.” Yes, prior to that time they did allow their currency to devalue rather precipitously, but if you look back and think about it, they were faced with something of a crisis at the time. Most currencies do fall during periods of economic stress.

Don’t get me wrong. The United States and China have a several-page list of issues that need to be worked out between them. If you read my recent book on China, you learned about more than a few of those problems. But given that the Federal Reserve has been the most egregious currency manipulator in the world over the last five years, hearing the pot calling the kettle black probably sticks in the craw of most non-US citizens. I understand it makes for a great populist harangue. It’s always easiest to blame our problems on someone else. But it doesn’t get us anywhere we want to go.

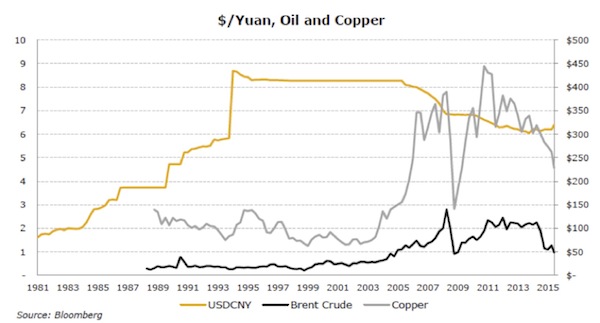

Back to the main story. Let’s look at this fascinating chart from my friend Chris Whalen over at the Kroll Bond Rating Agency:

Chris writes:

With the end of QE in sight in 2014, the dollar began to climb against most major currencies with the exception of the yuan, which remained effectively pegged against the dollar because of intervention by the PBOC. The yuan has, in fact, appreciated steadily against the dollar since 2006 and continued to move higher within the managed foreign exchange regime maintained by the Chinese government. Until last week, the PBOC had been using its foreign exchange reserves to cope with the increased demand for dollars from domestic investors. The decision to end the defense of the currency has economic as well as financial ramifications. For example, investors are starting to wonder just how much foreign currency debt China has accumulated to fund infrastructure investment as well as foreign ventures, and whether this total is reflected in official debt statistics.

Oil and copper are priced in dollars. From the point of view of China, and much of the rest of the world, oil is up several times in the last 15 years, and copper is up 2 to 3 times, even after the recent selloffs. From an inflation-adjusted standpoint, the rest of the world just sees things as getting back to normal. A strong dollar can do that.

Chinese Déjà Vu

Trump’s China complaints are nothing new. I wrote an entire issue on this topic five years ago (and Jonathan Tepper and I dealt with it at length in both Endgame and Code Red.) At that time, economist Paul Krugman and a group of senators led by New York Democrat Chuck Schumer wanted to impose a 25% tariff on Chinese imports. This is from my March 20, 2010, issue:

I probably shouldn’t take on a Nobel Laureate who got his prize for his work on trade, but this truly scares me. People pay attention to this nonsense, including the five senators, led by Schumer of New York, who want to start the process of targeting China.

First, the Chinese have got to be wondering what they have to do to make these guys happy. In 2005 they were demanding a 30% revaluation of the Chinese yuan. And over the next three years the yuan actually rose by 22% at a gradual and sustained pace. Then the credit crisis hit, and China again pegged their currency [even as the dollar got weaker!]. From their standpoint, what else were they to do? Force their country into a recession to appease our politicians?

They responded by a massive forcing of loans to their businesses and governments and huge infrastructure projects. Kind of like our stimulus, except they got a lot more infrastructure to show for their money. It remains to be seen how wise that policy was, and how large the bad (non-performing) loans will be that came from that push – just as there are those (your humble analyst included) who do not think the way we went about the stimulus plan in the US was the wisest allocation of capital.

But the reality is that the Chinese will do what is in their best interest. I wrote in 2005 that the yuan would rise slowly over time. The political posturing of Schumer, et al., was counterproductive then, and it still is now.

My prediction? The Chinese will begin to allow the yuan to rise again sometime this year, just as they did three years ago, because it will be to their advantage. A stronger yuan will act as a buffer to inflation, which they may face due to the massive stimulus they created. They are going to need some help in that area. But it will be 5–7% a year, so as not to create a shock to their export economy. Not 25% at one time. And at some point they will allow the yuan to float against the dollar. They know they will have to in order to get the currency status they want.

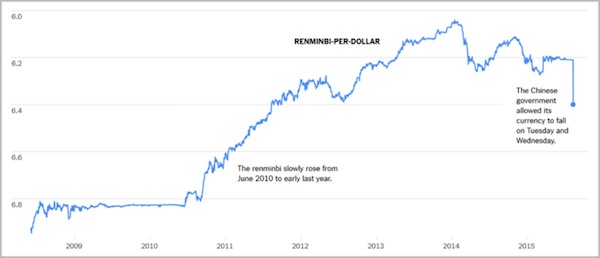

Back then, it was Schumer and Krugman who wanted to “rein in” China. Now we have Trump saying more or less the same things. Look at what happened in the intervening five years, in this chart from Krugman’s home-base New York Times.

And sure enough, right on schedule and as I predicted in 2010, the RMB began to slowly rise and rose through early 2014. This was about the same time that “China stopped acting Chinese,” as I wrote earlier this month. At about that time, China Beige Book detected a noticeable shift in Chinese business behavior, when companies stopped using the government’s stimulus to add new capacity.

Our hypothesis, you may recall, is that the Chinese monetary stimulus began going into stocks instead of capital improvement projects. That inflow led to the stock bubble that has popped over the last few weeks. Which resulted in an apparent panic in the halls of Chinese government.

Code Red at the PBOC

Sorting through the approximately 47,000 China reports people sent me in the last 10 days, I see two broad categories of analysis.

In one corner are those who think Beijing is frantic to juice its economy. They point to the disappointing export numbers that came out shortly before the PBOC currency action. The theory is that letting the renminbi fall a bit will help keep the export machine running. For what it’s worth, the Chinese economy is indeed slowing down. This morning we learned that their manufacturing index had registered below 50 for the sixth straight month.

In the other corner are those who say the PBOC action has little or nothing to do with China’s present economic situation. It was instead a key step in efforts to internationalize the renminbi and see it added to the International Monetary Fund’s reserve currency basket – the so-called Special Drawing Rights or SDR.

Those who read Code Red, my 2013 book with Jonathan Tepper, will probably guess that I lean toward the second interpretation. I’ve been anticipating competitive currency devaluations from many countries. The term “currency war” might be too strong, but I expect more such moves to be made. As Japan has demonstrated, devaluation is the logical next step in the monetary game everyone is playing.

(Speaking of Japan, we learned this week that their GDP shrank at a 1.6% annual pace last quarter. Slowing exports were a big factor, and you can bet that some of the missing export volume would have gone to China.)

I wrote in 2013 and have been saying since that if China does float the RMB, the currency will go down in value, not up. The amount of capital tied up in China that would like to move offshore will make the recent currency moves seem like a summer picnic.

Every time the Chinese open the currency-trading window, their currency is going to slip to the bottom of the band. It is hardly currency manipulation if the market is telling you that your currency is valued too high. Even China, with its massive dollar reserves, does not have enough money to maintain its currency at its current value should they try to float the RMB. See for reference Great Britain’s little run-in with George Soros, circa 1992.

So what is China up to? President Xi Jinping is trying to balance two conflicting objectives. He knows China’s closed economy is unsustainable and that they must liberalize their trade and monetary policies. That means letting market forces set things like the RMB exchange rate.

Letting markets rule is hard, even if you aren’t a communist. Xi governs a country of a billion-plus people who are accustomed to central planning. Going all the way to Adam Smith’s laissez faire isn’t in the cards, but even small steps won’t be easy.

On the other hand, more than a few Chinese have built their own versions of laissez faire. Those with money have found numerous ways to get it across the border in recent years. They have also bought hard assets, because they don’t trust the government to engineer a soft landing.

With capital controls that were leaky anyway and the economy slowing down, Beijing might have loosened the RMB band even if SDR inclusion weren’t on the table. The fact that it is on the table, and that the IMF had dropped heavy hints that China should let the RMB float, made now a good time to start the process.

I believe a free-floating renminbi is the ultimate goal, but the PBOC is still a long way from that point. They will let it adjust gradually. How far? If they believe their own statements, they will let the market answer that question.

What happens when Beijing doesn’t like the market’s answer? They will ignore the market and do whatever they think will maintain social stability.

While I was in the midst of writing this, George and Meredith Friedman (of Stratfor) stopped by the hotel here in New York for a brief visit. As is typical when we’re together, we immediately began to discuss the topic of the day, which was China’s currency issues. George sees the world through a geopolitical lens with an economic tint. I, on the other hand, see the world through an economic lens with a geopolitical tint.

George argues forcefully that Xi is ruthlessly attempting to restructure an economy that has allowed 20 to 25% of its citizens to achieve a middle-class lifestyle. Much of the rest of the country lives a lifestyle that is on par with that of Bolivia. The disparity between the coast and the rural interior areas is quite wide – a situation not entirely unlike the one Mao found himself in 70–80 years ago. The Chinese leadership remembers the lessons of that era, and Xi is determined not to allow the privileged few to put the system at risk.

I have written on numerous occasions about the absolutely staggering amount of money that has been leaving China, even with capital controls. We are talking tens if not hundreds of billions of dollars. The effects on global markets are truly breathtaking.

I saw one sign this week that underscores both Beijing’s challenges and its boldness. The New York Times reported on Aug. 16 that Chinese government agents have secretly visited expatriates in the US and pressured them to return to China. This behavior would be a violation of US law. The Obama administration reportedly demanded a halt to the activity.

China apparently regards some expatriates, especially those caught up in the recent anti-corruption drive, as fugitives from justice. That may be true, but it is also certainly true that these people brought a lot of Chinese capital to the US with them. And capital leaving the country doesn’t further Beijing’s larger objectives.

While I doubt Chinese expatriates have removed enough cash from China to truly move the country’s needle, China’s aggressive pursuit of them serves as a useful warning to others who might be planning such moves.

As an aside, I mentioned this item to George. He smiled and gave me that “you poor little naïve boy look” that he pulls off so well with me. “They know they can’t compel the former Chinese citizen to come home. They just ask how his parents or children are doing.” The message is understood.

Hard Landing or Soft?

Much depends on how well China juggles all the ponderous economic balls it has in the air, and by “much” I mean “the entire global economy.” We should all hope they get it right.

If all goes well over the next year or so,

- The PBOC will gradually take its hand off the scale and let the renminbi float freely,

- Beijing will find ways to swing the economy from export-driven to consumer-driven,

- Chinese stock valuations will return to a more realistic level,

- Debt levels will hold steady or shrink, and

- The nations that have been shipping raw materials to China will make their own adjustments.

A lot to ask for? Yes. We need all these things to happen, but some of them don’t coexist naturally.

For example, Chinese state and private debt currently total about 300% of GDP. If you think that the GDP number they publish is too high, the debt percentage goes even higher. China has a lot of debt any way you look at it, and much of it is dollar-denominated.

A devalued renminbi makes dollar-denominated debt more expensive. Chinese companies that borrowed dollars just saw their debt-servicing costs jump higher. Those who complied with Beijing’s command to seek domestic revenue instead of exports will feel the squeeze the most.

Far be it from me to underestimate the Chinese leadership’s management ability or their willingness to force change. They have done the seemingly impossible before. They might do it again, but their odds are certainly not improving and may be getting worse.

Chinese leaders often give with one hand and take away with the other. I can easily imagine them opening up the currency as the IMF and the West want, while at the same time working behind the scenes to “discourage” Chinese citizens from taking advantage of the new opportunities that result.

If that’s the plan, it will likely be negative for Western markets that have attracted Chinese assets in recent years. London and New York penthouses – which are being emptied of Russians – may have even fewer prospective buyers.

That’s small potatoes, though. Our real problems will start if China suffers a hard landing or their growth falls to 1 or 2%. I am not predicting that, but we need to consider the possibility. The chances are more than remote.

Monetary Missiles

You can debate whether China is serious about opening its closed economy to market forces. I think it’s clear that at the very least they want to look as ifthey are opening the closed economy. That the PBOC held a news conference to explain its actions last week was significant, despite the brevity of the explanation.

Does Beijing have a detailed road map that lays out a specific route from here to there? I don’t think so. I think they realize the markets would outguess any predetermined path. Instead, they’re taking one step at a time, observing the results, and then taking another step.

That is a smart strategy. The risk is that it could lead the Chinese leadership to places it doesn’t want to go. Then what?

The Chinese may have stopped acting Chinese, but on one level nothing has changed. Maintaining social order and keeping the current regime in power are still the top priorities. They will not let the markets put those goals in danger.

I have said for a long time that the US economy will muddle through all our domestic challenges and that our main risks come from exogenous shocks. A China hard landing is one of the top two such possible shocks. The other is a hard, sudden Eurozone breakup.

Either development would almost certainly push the US into a recession, and a global recession would follow. Global growth has recently fallen to the 2% range, which is actually quite troubling. If you have invested some money in emerging markets, you’ve probably noticed that there is true panic taking hold in them.

The European risk may have diminished, but it is still there. Greece is not the only problem. The catastrophe would be a Greece-like crisis in Italy, Spain, or France. The IMF and Germany put together could not paper over those debts.

If there are simultaneous shocks in both China and Europe, we will see a deep global recession. That will spark a real currency war. The small skirmishes we’ve seen so far are tiny in comparison to the monetary missiles that central banks would launch at each other.

Every Central Banker for Himself

The headline on Bloomberg at the close of the markets today is “Stocks fall most in four years as China dread sinks global markets,” with the article talking about the fall in emerging markets leading the US stock market down. Shades of 1998. The US markets were down over 3% today, culminating in the worst week in four years.

“To energy shares already snared in a bear market, add semiconductor stocks, which crossed the threshold by capping a decline of more than 20 percent. Apple Inc. also entered a bear market, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average entered a so-called correction with a decline of 10 percent from its last record. Biotechnology, small caps, media, transportation and commodity companies have also entered corrections.” (Bloomberg)

I’ve been talking about this sort of outcome for well over a year. It wasn’t all that long ago that the governor of the Central Bank of India, Raghuram Rajan, gave a controversial speech lecturing the Federal Reserve on the effects of US monetary policy on global markets. He warned that the weak monetary policy of the US Federal Reserve was going to create a great deal of damage in emerging markets and that we wouldn’t like the result.

It wasn’t long after that US Fed Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer replied in a major monetary speech. Let me translate what he said into comprehensible English:

“Rajan, I understand your concern, but you need to understand that we have bigger fish to fry and that we are going to run US monetary policy for our own benefit. Stop whining and figure it out.”

Understand, Fischer is at the very top of the pantheon of economic gods of the world. Rajan is one of the most respected economists and central bankers in the emerging-market world. This was no ordinary exchange.

I have written at least four letters about the probability of problems developing in the emerging-market world because of US Federal Reserve policy, and I have detailed the links between our policy and problems in those countries’ economies. Now, we may be on the verge of a crisis.

The low rates and massive amounts of money created by quantitative easing in the US showed up in emerging markets, pushing down their rates and driving up their currencies and markets. Just as Rajan (and I) predicted, once the quantitative easing was taken away, the tremors in the emerging markets began, and those waves are now breaking on our own shores. The putative culprit is China, but at the root of the problem are serious liquidity problems in emerging markets. China’s actions just heighten those concerns.

As an aside, people are wondering why the euro and the yen have recently been strengthening against the dollar. It’s because the US stock market is finally rolling over, and money is going to those areas of the world where quantitative easing is still being practiced with a vengeance. Is that logical? Please, don’t try to tell the markets to be logical. Market players have bought the narrative that quantitative easing means a rising stock market, and they’re going to stick to that narrative until it falls flat on its face. The markets can deal with only one narrative at a time.

Donald Trump wants to “rein in” China. Exactly how will anybody rein in anything if we tumble into another global recession, when it will be every country for itself? Not even Donald Trump knows how to make trouble on that scale.