by Julio Escolano, Laura Jaramillo, Carlos Mulas-Granados and Gilbert Terrier

Posted previously at VoxEU 27 February 2015

Fiscal consolidation is back at the top of the policy agenda. This column provides historical context by examining 91 episodes of fiscal consolidation in advanced and developing economies between 1945 and 2012. By focusing on cases in which the adjustment was necessary and desired in order to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio, the authors find larger average fiscal adjustments than previous studies. Most consolidation episodes resulted in stabilisation of the debt-to-GDP ratio, but at a new, higher level.

High public debt is one of the legacies from the Great Recession that is becoming a pressing issue in the wake of the economic recovery. According the latest IMF’s Fiscal Monitor (October 2014) the public debt ratio of the G-7 is close to 120 percent of GDP and that of the group of advanced economies near 106 percent of GDP. The Euro area as a whole is estimated to have finished 2014 with an average public debt ratio equivalent to 96 percent of GDP. Five years of strong fiscal efforts have stabilised aggregate debt levels, but today, several countries still face the challenge of restoring debt sustainability by continuing with their fiscal adjustment plans.

In this context, the debate around fiscal consolidation is far from over. The VoxEU debate “Has Austerity Gone Too Far?” (Corsetti 2012) has been reflecting the conflicting positions. While some contributors have focused on the characteristics of the fiscal consolidation needed to bring public debt down from historically high levels (Buti and Pench 2012), others have examined the effects of alternative strategies on economic performance (Van Reenen 2012 and Cottarelli 2012) which tend to be more negative in the presence of credit constraints which typically follow financial crises (Baldacci et al. 2013a and 2013b). Adjustment fatigue is setting in within some of the countries hardest hit by the crisis, but the debate about the feasibility of large and sustained fiscal adjustment has also become heated in other countries.

Putting fiscal consolidation in context

In this debate, a crucial question remains to be answered: How much fiscal adjustment is a lot? To answer this question, a relevant angle is to look at what size of fiscal adjustment has been actually feasible in the past. Answering this question is precisely the subject of our latest paper (Escolano et al. 2014). In this contribution we take stock of past consolidation episodes in terms of the size of fiscal adjustments, their duration, and the factors that have accompanied such adjustments.

Our approach adds to the existing literature in several ways.

- First, we draw lessons from a broad set of consolidation episodes by looking at both advanced and developing countries, and including a time period that spans from 1945 to 2012.

- Second, we make a very careful selection of the relevant episodes by choosing consolidation episodes where countries needed and wanted to adjust in order to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio.

This is a major novelty, since most papers in the literature looked at the characteristics (size, duration, composition, etc.) of all improvements in the primary balance, regardless of whether the country really needed and wanted to adjust.

This choice by previous authors played down the average size achieved by past adjustments. Instead, we looked at those episodes in which countries had large primary gaps (defined as the difference between the actual primary balance and the level of primary balance that would stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio); and selected only those cases in which countries went beyond pure intentions and showed consistent reductions in their cyclically adjusted primary deficits.

Looking at this set of 91 consolidation episodes that occurred in advanced and developing economies between 1945 and 2012, we found that in most cases fiscal adjustments were sizable and larger than previously identified by other studies. In at least half of the episodes, countries managed to improve their primary balance by 5.4% of GDP (4.8% of GDP in cyclically adjusted terms). And in 25% of cases, the size of the overall deficit reduction was around 8% of GDP.

Debt stabilisation at new, higher levels

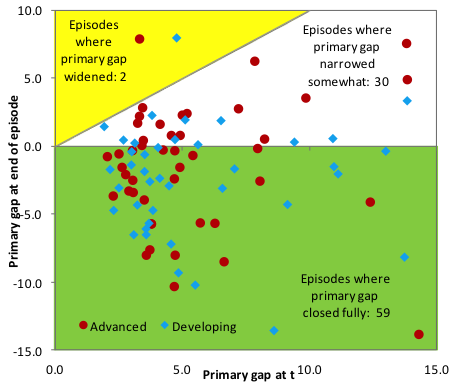

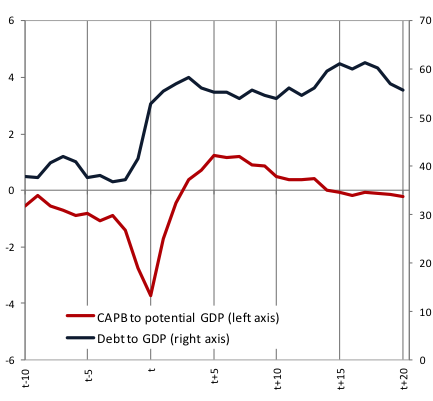

The size of the fiscal adjustment implemented during those episodes was enough to close the primary gap in two-thirds of cases (see Figures 1 and 2). This implies that debt stabilised, and in most cases was put on a downward trend. But debt-to-GDP ratios did not return to initial levels. While countries kept primary balances well above those observed before the adjustment episode, they did not sustain primary balances at the highest levels for prolonged periods of time. This suggests that countries tend to make substantial efforts to stabilise debt but, once this is achieved, they cease consolidation efforts and do not necessarily seek to get back to the lower initial debt-to-GDP ratio.

Figure 1. Primary gaps at t and end of the episode (% of GDP)

Figure 2. Debt and cyclically adjusted primary balance, median across episodes

Factors affecting fiscal consolidation

Finally, in our paper, we also looked at what factors were associated with the size of fiscal adjustments. Based on regression analysis, we found that fiscal adjustment was larger the greater the initial deficit, and that a sustained approach to deficit reduction increases the size of total consolidation. The results also show that fiscal adjustment tended to be higher when accompanied by an easing of monetary conditions (as measured through a reduction in short-term interest rates) and, to a lesser extent, an improvement of credit conditions (measured as the change in credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP), especially in advanced economies.

Concluding remarks

So, how much is a lot? The historical evidence indicates that it depends greatly on how much is needed. Countries adjust as much as they need to regain control over their increasing debt levels. After that, once debt is stabilised, adjustment efforts seem to run out of steam.

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, nor to its Executive Board, or its management.

References

Baldacci, E, S Gupta, and C Mulas-Granados (2013a), “Debt Reduction, Fiscal Adjustments and Growth in Credit Constrained-Economies”, IMF Working Paper 13/238.

Baldacci, E, S Gupta, and C Mulas-Granados (2013b), “Fiscal adjustment and growth: Beware of the credit constraints”, VoxEU.org, 31 March.

Buti, M and L R Pench (2012), “Fiscal austerity and policy credibility”, VoxEU.org, 20 April.

Corsetti, G (2012), “Has austerity gone too far?”, VoxEU.org, 2 April.

Cottarelli, C (2012), “The austerity debate: Festina lente!”, VoxEU.org, 20 April.

Escolano, J, L Jaramillo, C Mulas-Granados, and G Terrier (2014), “How Much is a Lot? Historical Evidence on the Size of Fiscal Adjustments”, IMF Working Paper 14/179.

Van Reenen, J (2012), “Fiscal consolidation: Too much of a good thing?”, VoxEU.org, 27 April.