from the Chicago Fed

— this post authored by Itzik Fadlon, Shanthi Ramnath, Patricia K. Tong, and Lisa Camner McKay

The death of a spouse results in a considerable decline in average income for the surviving spouse. The Social Security survivors benefits program compensates the surviving spouse, most often a woman, for almost all of the lost income, allowing them to work less, but many widows who are not yet eligible for the program struggle to meet their financial needs.

Losing a spouse is devastating. In addition to the emotional grief and personal loss, it also presents a real financial risk to many households. This risk primarily affects women because they are much more likely to be the survivor: In 2016, 78% of all surviving spouses were widows. Women also earn less than men, on average, making the income loss more significant. For individuals aged 55 to 64, wage data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that on average, women’s yearly earnings are about three-quarters of what men earn.[1]

The authors calculate that Social Security survivors benefits almost fully compensate widows for their income losses from the death of their spouse.

The Social Security survivors benefits program, designed to protect against income losses from the death of a spouse, has rapidly grown into one of the largest safety-net programs in the United States. Yet, there is virtually no causal evidence studying the economic effects of this program. This is the project described in a recent research paper by Itzik Fadlon, Shanthi P. Ramnath, and Patricia K. Tong.[2] The authors study the economic consequences of widowhood and the role that Social Security survivors benefits play in protecting people against the financial shock of this major life event. Fadlon, Ramnath, and Tong find that spousal death results in a considerable decline in household income and that rates of financial insolvency double. The conclusion is clear: Losing a spouse poses real economic hardship. Once surviving spouses become eligible for Social Security’s survivor’s benefits at age 60, however, they are almost fully compensated for their income loss, which allows them to decrease the amount they work (a form of self-insurance). The authors’ analysis suggests that economic outcomes for widows would improve if survivor’s benefits were offered earlier.

Economic consequences of the death of a spouse

Fadlon, Ramnath, and Tong are interested in two key economic outcomes following the death of a spouse. First, they want to know how households’ income changes. Using administrative tax records, they include a large number of different sources of income, including wages, interest, capital income, Social Security income, unemployment benefits, and withdrawals from retirement savings accounts. Second, they measure financial insolvency by looking at whether the widow received Form 1009-C, “Cancellation of Debt.” This form is issued by creditors when debt is canceled, such as due to bankruptcy, foreclosure, or debt relief, and thus indicates that the widow had debt that was not being paid.

To measure how the death of a spouse affects these two economic indicators, Fadlon, Ramnath, and Tong compare the outcomes of two groups of women between the ages of 50 and 70. The first group of 63,700 households lost their spouse in 2002 or 2003 (the treatment group), while the second group of 74,200 households would lose their spouse four years later, in 2006 or 2007 (the control group). The authors then use the outcomes of the control group to construct counterfactual outcomes for the treatment group, which they compare to the treatment group’s actual outcomes. The goal of this analysis is to isolate the causal effect of spousal death.

Individual annual income falls by an average of $5,500 after the death of a spouse and remains at this level for the next two years.

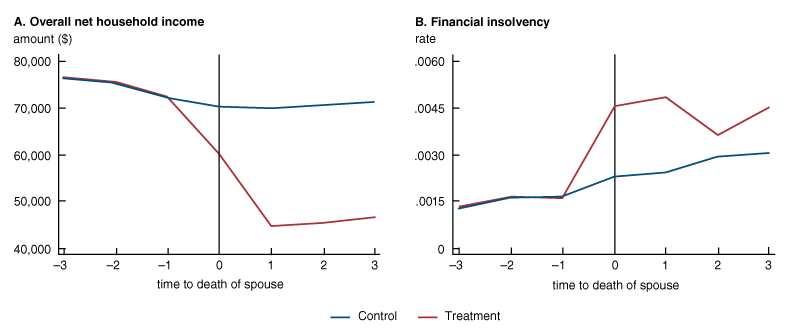

The results show that widowhood is a financial struggle for many. The average annual household income in the three years before a spouse dies is about $75,000 (figure 1). In the three years after the spouse dies, it averages $47,000 a year. But these households have one fewer person and so need less income to maintain the same standard of living. After adjusting for household size, the authors find that individual income falls by an average of $5,500 a year after the death of a spouse and remains at this level for the next two years. This translates to a persistent decline of 11% in an individual’s annual income.

1. Effect of spousal death on household income and financial insolvency

Notes: This figure shows how household income and financial insolvency evolve after the death of a spouse, indicated by the vertical line at time 0. For the treatment group, t = 3 is three years after the death of their spouse, while for the control group, t = 3 is one year prior to the death of their spouse. Panel A shows that household income declines slightly before the death of a spouse, then declines rapidly. Panel B shows that the rate of financial insolvency is considerably higher for the treatment group than the control group.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago staff presentation.

The rate of financial insolvency also gets worse after the death of a spouse. About 4.5 out of every 1,000 households experience financial insolvency in the year of their spouse’s death (see figure 1), which means that their rate of insolvency is roughly double that of the control group. Together, these results show that Americans are exposed to significant economic risk after the death of a spouse.

Financial protection from Social Security survivors benefits

The Social Security survivors benefits program gives surviving spouses the retirement benefits due to the deceased based on the deceased’s earnings history. Eligibility for these benefits begins at age 60 in most cases. To analyze how well the program works at protecting widows against economic losses, Fadlon, Ramnath, and Tong look at a variety of economic outcomes for newly widowed survivors whose spouse died in the previous one or two years. So if a woman’s husband dies when the wife has just turned 59, what are her economic outcomes in the next year? And how do they compare with those of a woman whose husband dies when she has just turned 60 and therefore is eligible?

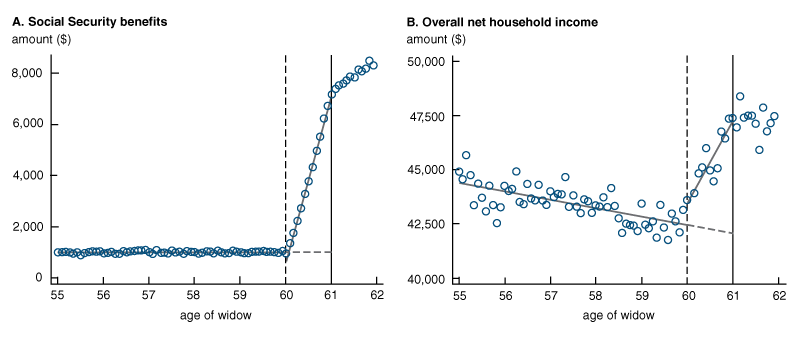

The authors show that the percentage of women claiming Social Security benefits increases by 51 percentage points at age 60, the first age of eligibility, meaning that half of these women claim their benefits as soon as they can. The effect on their income is immediate – they gain an average of $4,804, taking their income from roughly $42,300 to $47,200, an increase of 11% (see figure 2). This suggests that Social Security survivors benefits make a big difference for eligible widows, almost fully compensating them for their income losses from the death of their spouse.

The authors make these calculations based on a counterfactual: They look at the behavior of newly widowed spouses between the ages of 55 and 59 (who are ineligible for survivors benefits) and then extend the trend line from that data through age 61, creating a counterfactual that imagines what the outcome would be if there were no survivors benefits. This is the dashed line in figure 2. Then the authors calculate the difference between this counterfactual and the actual outcomes for widows at age 61 to estimate the effect of the benefits program.

2. Effect of eligibility for survivors benefits on benefit claims and household income

Notes: This figure plots household outcomes in the one to two years just after a husband’s death. Because eligibility occurs at exactly age 60 but the data (from tax returns) are collected once at the end of the year, it takes until age 61 for the full effect of survivors benefits to become clear. The solid line between ages 60 and 61 is the trend line for the actual data. The dashed line represents the counterfactual behavior in the absence of survivors benefits. Thus the effect of benefit eligibility is represented by the vertical gap between the solid and the dashed gray lines at age 61. Note that this data include all widows, including those who do not choose to claim survivors benefits at age 60.

Source: Fadlon, Ramnath, and Tong (2019).

Labor supply and the life insurance market

Fadlon, Ramnath, and Tong are also interested in newly widowed spouses’ decisions about how much to work, because this provides some information about how well the life insurance market is working. If the life insurance market is working perfectly, there should be no change in labor supply between the just-ineligible and the just-eligible widows, the authors argue. This is because people would be able to buy just the right amount of insurance to cover their consumption needs in case their spouse dies until they become eligible for survivors benefits.

However, the authors find that there is a noticeable change in the amount widows work once they receive survivors benefits: On average, their yearly earnings decline by $1,751. Because the authors estimate that their counterfactual earnings (i.e., their earnings if there were no survivors benefits) would be $18,550, this means that their labor supply declines by 9% as a result of receiving survivors benefits.

Taken together, the fact that household income increases and the labor supply decreases for widows receiving survivors benefits captures “the protective insurance role of survivors benefits against the immediate adverse financial consequences of a spousal death,” the authors write. It also suggests that people don’t buy enough life insurance to allow widows to not have to work more after their spouse dies.

Widowed households’ liquidity problem

Fadlon, Ramnath, and Tong also study the effect of the Social Security survivors benefits program on spouses who were widowed six to ten years before they become eligible. These widows have had years to adjust to the loss of their spouse and anticipate the timing of their government benefits. Economic theory predicts that ideally, most people prefer to “smooth” their consumption over time, consuming approximately the same amount yesterday as today and tomorrow. This is practical because many household expenses are roughly the same month to month (mortgage payments, food costs) and this allows people to keep their lifestyle relatively constant. For similar reasons, people usually smooth their labor supply. This model of economic behavior says that knowing that they will be eligible for government benefits at age 60, widows will attempt to smooth their consumption and labor supply using their savings and by borrowing before age 60. Of course, if households have enough savings or access to credit markets, then they need not change their work behavior much when they become eligible for survivors benefits.

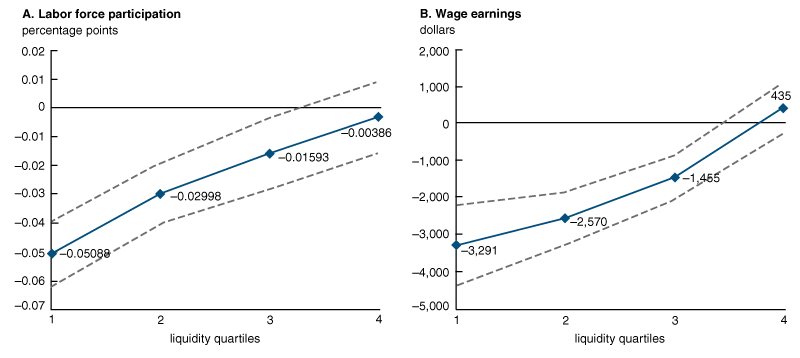

However, in the sample of widows that the authors study, only households in the top quartile of savings actually keep their labor supply and earnings the same when they reach eligibility. These households have enough savings to smooth their income and labor after the death of their spouse, and so they don’t need to adjust their behavior. Households in the lowest quartile of savings, in contrast, change their behavior quite a bit when they become eligible for benefits: Their labor force participation falls by 5 percentage points and their average yearly earnings by $3,291 (see figure 3). The authors find suggestive evidence that these households don’t have enough savings and are unable to borrow to keep them afloat when their spouse dies – in economic terms, they have a liquidity problem. Therefore, when they are finally eligible for benefits, they adjust their work behavior immediately.

3. Labor supply responses by household liquidity

Notes: The x-axis divides the households into quartiles by their level of liquidity, as measured by unearned income (e.g., capital gains, interest income). In panel A, the dots plot the change in labor force participation after households become eligible for survivors benefits. The lowest quartile decreases participation by 5 percentage points, whereas the top quartile doesn’t change behavior. In panel B, the dots plot the change in wage earnings after households become eligible for survivors benefits. The lowest quartile’s wage earnings decline by $3,291, while the highest wage earnings do not meaningfully change. The dashed lines show 95% confidence intervals.

Source: Fadlon, Ramnath, and Tong (2019).

Conclusion

When a wife loses her husband before age 60, she must rely on her savings, wages, and any life insurance the couple had previously purchased to meet her economic commitments. Because the life insurance market and credit market do not work perfectly, that usually isn’t enough, and widows suffer financially as a result. Fadlon, Ramnath, and Tong’s findings imply that lowering the eligibility age for the Social Security survivors benefits program – essentially providing smaller benefits over a longer period – could be helpful for households going through difficult times.

Notes

Research by Itzik Fadlon, University of California, San Diego and National Bureau of Economic Research, Shanthi P. Ramnath, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, and Patricia K. Tong, RAND Corporation

Summary by Lisa Camner McKay, economics writer

Footnotes

1 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020, “Usual weekly earnings of wage and salary workers: Fourth quarter 2019,” economic news release, Washington, DC, January 17, table 3, available online.

2 Itzik Fadlon, Shanthi P. Ramnath, and Patricia K. Tong, 2019, “Market inefficiency and household labor supply: Evidence from Social Security’s survivor’s benefits,” National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper, No. 25586, revised June. Crossref

Source

https://www.chicagofed.org/publications/chicago-fed-letter/2020/438

Disclaimer

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago or the Federal Reserve System.