Written by Steven Hansen

Export and Import container counts were very weak in February 2014. Worse, the rolling averages are decelerating and the year-to-date counts are contracting over 2013 levels.

For the month of February 2014:

- the economically intuitive imports growth decelerated 11.6% month-over-month, is down 7.0% compared to February 2013, and down 1.2% year-to-date. There is a direct linkage between imports and USA economic activity – and growth in imports foretells real economic growth.

- Export growth (which is an indicator of competitiveness and global economic growth) decelerated 1.7% month-over-month, is down 2.4% compared to February 2013, and is down 1.5% year-to-date.

Unadjusted 3 Month Rolling Average for Container Counts Year-over-Year Change (comparing the 3 month average one year ago to the current 3 month average) – Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach Combined – Imports (red line) and Exports (blue line)

/images/z container4.PNG

There is reasonable correlation between the container counts and the US Census trade data also being analyzed by Econintersect. But trade data lags several months after the more timely container counts.

Unadjusted Year-over-Year Change in Container Counts – Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach Combined – Imports (red line) and Exports (blue bars)

/images/z container1.PNG

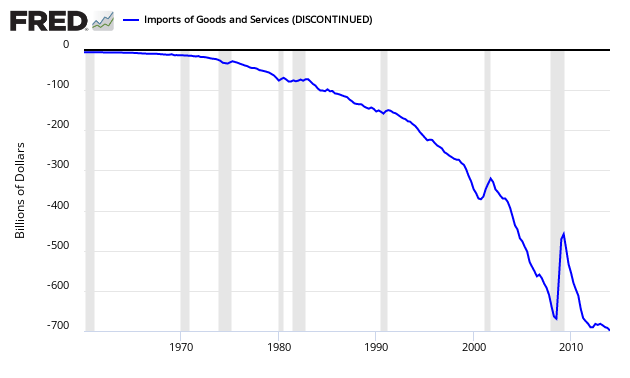

Econintersect considers import and exports significant elements in determining economic health (please see caveats below). the takeaway from the graphs below is that imports still have not returned to pre-2007 recession levels, while exports did recover.

Unadjusted Import Container Counts – Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach Combined

/images/z container2.PNG

Unadjusted Export Container Counts – Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach Combined

/images/z container3.png

The Ports of LA and Long Beach account for much (approximately 40%) of the container movement into and out of the United States – and these two ports report their data significantly earlier than other USA ports. Most of the manufactured goods move between countries in sea containers (except larger rolling items such as automobiles). This pulse point is an early indicator of the health of the economy.

Containers come in many sizes so a uniform method involves expressing the volume of containers in TEU, the volume of a standard 20 foot long sea container. Thus a standard 40 foot container would be 2 TEU.

There is a good correlation between container counts and trade data (the US Census trade data is shown on the graph below). Using container counts gives a two month advance window on trade data.

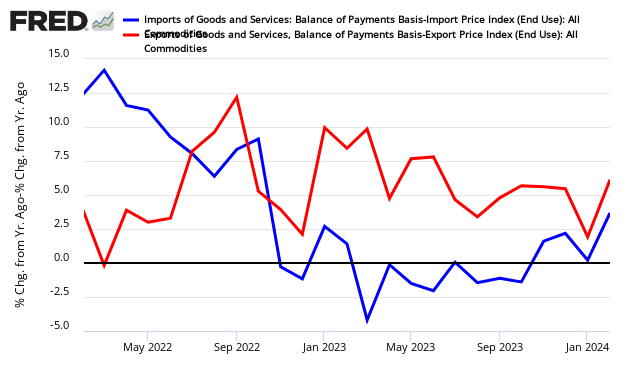

Inflation Adjusted Year-over-Year Change Imports (blue line) and Exports (red line)

Transport has been languishing with very weak growth.

Caveats on the Use of Container Counts

These are extraordinary times with historical data confused by a massive depression and significant monetary and fiscal intervention by government. Further containers are a relatively new technology and had a 14 year continuous growth streak from 1993 to 2006. There is not enough history to make any associations with economic growth – and we must assume a correlation exists.

Further, it is impossible from this data to understand commodity or goods breakdown (e.g. what is the contents in the containers). Any expansion or contraction cannot be analyzed to understand causation.

Imports are a particularly good tool to view the Main Street economy. Imports overreact to economic changes much like a double ETF making movements easy to see.

Contracting imports historically is a recession marker, as consumers and businesses start to hunker down. Main Street and Wall Street are not necessarily in phase and imports can reflect the direction for Main Street when Wall Street may be saying something different. During some recessions, consumers and businesses hunkered down before the Wall Street recession hit – and in the 2007 recession the contraction began 10 months into the recession.

Above graph with current data:

Imports of Goods and Services

Econintersect determines the month-over-month change by subtracting the current month’s year-over-year change from the previous month’s year-over-year change. This is the best of the bad options available to determine month-over-month trends – as the preferred methodology would be to use multi-year data (but the New Normal effects and the Great Recession distort historical data).

Related Articles: